Patients, caregivers, and physicians are shown at a Patient Support Group Meeting in India. The Max Foundation established Friends of Max, a charitable trust that provides patient support groups. It has multiple chapters in India that serve those who are impacted by chronic myeloid leukemia or gastrointestinal stromal tumors. (Photo courtesy of The Max Foundation)

Imagine this for a moment: You have a hematologic malignancy that will be fatal if left untreated. A safe and effective therapy exists, but you cannot access the treatment because it is not available in your country.

Many patients in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) face these very challenges surrounding cancer care access, availability, and affordability. For example, less than 15% of low-income countries reported “comprehensive treatment services for cancer were available in the public health system” in 2019, compared with more than 90% of high-income countries, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Pan American Health Organization.1

“There’s only one thing worse than hearing the word ‘cancer,’” said Pat Garcia-Gonzalez, Chief Executive Officer of The Max Foundation. “It’s to hear that there are treatments, but because of where you are, you can’t have them.”

Addressing this issue informs the core mission of The Max Foundation, a nonprofit and international nongovernmental organization that works to expand access to treatment and diagnostics for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) and other malignancies in LMICs.

“At The Max Foundation, we aim to be that bridge between these resources and patients, especially by bringing access to these medicines, technology, and support for patients in every corner of the world,” Garcia-Gonzalez said.

The foundation provides lifesaving medication at no cost to patients in more than 70 LMICs where access is not available locally, with approximately 35,000 patients receiving treatment each year. Since it began in 1997, the foundation has grown from a website offering resources into a global model for providing access to diagnostics, treatment, medication, care, and social support.

“Our mission is to accelerate health equity. We don’t want patients to have to wait 20 years—or never— to receive these medicines,” Garcia-Gonzalez said. “We say our vision is a world where geography is not destiny.”

Remembering Max

Maximiliano “Max” M. Rivarola, Ms. Garcia-Gonzalez’s stepson, and the namesake of The Max Foundation, is shown. (All photos courtesy of The Max Foundation)

The story of The Max Foundation begins with its namesake, Maximiliano “Max” M. Rivarola, Garcia-Gonzalez’s stepson. He was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, on October 19, 1973, and grew up attending a school on the outskirts of Buenos Aires. He was a good student, had many friends, and loved to ski and play rugby and tennis, according to his biography from Friends of Max.2

However, when Max was diagnosed with CML at age 14, there was only one potential avenue for a cure.

“The only hope we had was that he would have a bone marrow transplant, and that we would find a donor, and then he would survive the transplant,” Garcia-Gonzalez said.

Max’s family brought him to the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston to receive treatment as they searched the world’s bone marrow registries for a matched donor.

“We looked for two and a half years for a match,” Garcia-Gonzalez said. “We never found a match for Max.”

After years of searching for a matched donor, Max passed away on March 9, 1991, at the age of just 17.

“One doesn’t get over losing a child to cancer, nor does one get over a young mother losing their life, a sibling, a friend,” Garcia-Gonzalez wrote in an article on The Max Foundation’s website.3 “There is no closure, there is no moving on; one just adjusts to live with that, not by choice but because there is no other option. However, if there is something I am grateful for, it is for the opportunity to turn the rage and frustration of not being able to save him into fuel that stops other families from going through this tremendous pain.”

Building the Foundation

As Max’s family grieved, they realized they had learned much about the process of navigating a CML diagnosis and that it might be possible to use their experiences to help others.

Garcia-Gonzalez started The Max Foundation in 1997 as a “very grassroots website” to provide information and resources for patients and families who were navigating similar situations. Since its inception, the foundation has received emails daily from patients and families who have been told there is a treatment that can help them but that it is not available in their country, she said.

Pat Garcia-Gonzalez, CEO of The Max Foundation, is shown.

While Garcia-Gonzalez knew firsthand how these patients and their families were feeling when she started The Max Foundation, she was shocked to learn the extent of the challenges surrounding access to cancer care in many parts of the world.

“Most innovative treatments for cancer that come to the market today will never reach most patients in the world,” she said. “They’re not even registered in most countries in the world. There is no way these people can access them.”

For example, 32% of cancer medications on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines are “available only at full cost” in LMICs, while 5% are “completely unavailable,” according to a 2021 study.4

As Garcia-Gonzalez began to look more deeply into the issue, she found the limitations were even more widespread than she realized.

“I assumed that companies had global access strategies, and I would ask them, ‘What’s your global access strategy?’ Their global access strategy is perhaps 40 countries and the others, no plans,” she said. “I think that’s not acceptable.”

These challenges would fundamentally shape The Max Foundation and inform its mission as more treatments became available for patients with CML.

A ‘Big Breakthrough’

In 2001, the US Food and Drug Administration’s approval of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) imatinib, known by its brand name, Glivec, “revolutionized the treatment” of patients with CML by “converting a fatal cancer into a manageable condition,” according to Nida Ibqual and colleagues in a 2014 review article.5

The approval was a “big breakthrough,” and in 2001 the foundation entered a partnership with Novartis, the drug’s manufacturer, to “make sure no one in the world would go without this drug,” Garcia-Gonzalez said.

The partnership created the Glivec International Patient Assistance Program, a “direct-to-patient international drug donation program,” to provide cancer treatment for patients in more than 70 LMICs.6

“Our role in this program was to liaise with treating physicians in LMICs and make sure that patients met the program criteria,” Garcia-Gonzalez said, noting that the foundation developed a program to provide “thousands of patients access to imatinib.”

At left, Tenaye Alazar, a Max Foundation Local Program Coordinator based in Ethiopia, receives a gift from a patient. Alazar joined the foundation in 2016 as their first and only program coordinator in Ethiopia.

Free access to imatinib through The Max Foundation has been transformational for patients around the world. Temilola Owojuyigbe, MBBS, a Consultant Hematologist at the Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospitals Complex in Ile-Ife, Nigeria, reflected on the changes in care and survival since imatinib became available in Nigeria in 2003.

“The advent of the drugs has led to improved survival and quality of life, with a better safety profile and fewer side effects compared to conventional chemotherapy,” Dr. Owojuyigbe wrote in an article for The Max Foundation.7 “Most patients become anxious and fearful that their life is about to end and that they will not be able to work or enjoy life. However, due to the availability of the drugs, they have a happy story to tell. They can look back, be thankful, and look forward to the future with hope.”

Overcoming Diagnostic Challenges

By 2009, the foundation had been providing imatinib to patients around the world for several years, including 200 patients in Ethiopia.

However, when Garcia-Gonzalez met one of the foundation’s partner physicians in Ethiopia that year, she learned some surprising information about remaining barriers to treatment.

“He said, ‘I just need you to understand that for the 200 patients in your program, I have 400 others that don’t have a house to sell so they can come up with $600, so they can send their blood to Germany, so they can confirm the Philadelphia chromosome, so they can get into your program,’” Garcia-Gonzalez recalled.

The foundation set out on a mission to address the diagnostic challenges in Ethiopia, and by 2011, the organization was able to bring the necessary polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technology for diagnostics to the Black Lion Hospital in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

One of the very first patients diagnosed with CML by PCR in Ethiopia was a young medical student, Fisihatsion Tadesse, who later decided to become a hematologist when he received his medical degree.

“They did not have a hematology residency program in Addis Ababa at the Black Lion Hospital, but they opened one for him,” Garcia-Gonzalez said. “He now is one of three hematologists in Ethiopia, and he’s the director of the Hematology Department at Black Lion Hospital. He’s still in treatment, and he has a great response.”

Dr. Tadesse reflected on how the testing and treatment access shaped his life.

“I was, and still am, a beneficiary of The Max Foundation. I was diagnosed with CML when I was a first-year resident,” Dr. Tadesse said in a quote included in the foundation’s 2022-2026 strategic plan.6 “The lifesaving service [the foundation] provided was the inspiration that led me to study hematology and forever strive to pay the debt forward.”

Several years later, in 2017, the foundation launched the Spot On CML program to further expand access through a low-cost, paper-based diagnostic testing method that can be used in areas where molecular diagnostic equipment is not yet accessible or available.

The test was developed at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center by the lab of Jerald Radich, MD, who serves on the foundation’s Board of Directors and is an Associate Editor for Blood Cancers Today.

The test allows physicians to spot a patient’s blood onto the paper testing card, and the provider can then mail it to Dr. Radich’s lab for processing, providing “accurate diagnostic testing on the samples even after weeks of transport” and avoiding the potential challenges that can arise when shipping liquid samples.

The ‘Hope Index’

In some regions, the challenges for patients with cancer extend far beyond access to diagnostics and care. Shalini Subramanian, a Local Program Coordinator in India, provided insight on the social aspects of cancer in India.

“Patients feel isolated, as their illness sets them apart, discredits them in the eyes of others, and threatens their sense of identity,” Subramanian wrote in an article for The Max Foundation.8 “We hear stories of patients being denied opportunities for employment and accommodation due to their illness. Younger patients fear losing their careers and worry about future marriage proposals. A few even worry about losing their family and friends due to their illness.”

Because of these social challenges, the foundation worked with patients in India to establish Friends of Max, a charitable trust that provides patient support groups for people in India who are impacted by CML or gastrointestinal stromal tumors.

“Our main goal is to connect people who are living with cancer in a place where they feel their experiences and queries belong,” Subramanian wrote.8 “We want each of our patients to know they are not alone; together, we can overcome social stigma.”

These meetings can be the “lifeline that patients need to survive with cancer,” Garcia-Gonzalez said.

Beyond The Max Foundation’s direct impact on patients, its work can also help the clinicians who treat them.

“We cannot overestimate the importance of a program like this for hematologists and oncologists in LMICs,” Garcia-Gonzalez said. “Often, our patients are the only patients they can successfully treat. Sometimes we talk about the ‘hope index,’ we see that it allows them to continue to come to work every day.”

Alazar places a hat on a child. Alazar partners with physicians, provides counseling and education for patients on their disease and treatment, and oversees the Max Access Solutions program operation and supply chain in Ethiopia.

The “hope index” is key, she said. Giving access to diagnostics, treatments, and training encourages more medical students and trainees to specialize in oncology, as they feel they will have the tools to help their patients.

For example, a 2020 study showed patients who received imatinib through The Max Foundation had a five-year survival rate of 89%, which “compared favorably to the survival in high-income countries despite the challenges of delivering cancer care” in LMICs.9

The data challenge the perception that cancer care cannot be provided in the developing world, said Garcia-Gonzalez, who served as an author on the study.

“We have eradicated the survival disparity for CML in the world, which was thought to be impossible,” she said. “But it is actually possible.”

This has allowed The Max Foundation to serve as a platform for countries to build their own systems for cancer care, Garcia-Gonzalez said.

“In some of the countries, when we demonstrated that these treatments could be used, then the government stepped in and took responsibility,” she said. “We were able to hand over the program to the government, which, that’s what we want. We want to be this bridge until the governments are ready to support. We brought the treatments, we created the infrastructure, we trained [the] physicians, and then [we] handed over the program.”

A ‘Dream Has Come True’

As The Max Foundation grew and evolved over the years, it expanded its ability to provide second- and third-line treatments to patients throughout the world. Since 2018 the foundation has been able to provide access to dasatinib, nilotinib, ponatinib, and bosutinib through collaborations with manufacturers.

“If you asked what our dream was 10 years ago, our dream was that we could give any treatment that our patients needed … today, that dream has come true,” Garcia-Gonzalez said. “We are providing access to all the [TKIs] for CML patients.”

This year, as part of the CancerPath to Care collaboration with Novartis, the foundation is launching a program to provide access to asciminib, a first-in-class allosteric inhibitor of BCR::ABL1 kinase activity, for patients with CML in 36 LMICs.

“Reaching patients in LMICs requires operational excellence and deep commitment—The Max Foundation has a two-decade track record as a leader in treatment delivery,” Lutz Hegemann, MD, PhD, President of Global Health and Sustainability at Novartis, said in a news release. “We are proud of what our collaboration with The Max Foundation has achieved. We are committed to helping ensure that our innovative medicines are accessible to as many patients as possible, irrespective of where they live.”

The Max Foundation has also expanded its partnerships and the types of malignancies treated through the Humanitarian Partnership for Access to Cancer Treatment (PACT), which began in 2015 when the foundation partnered with five multinational pharmaceutical companies. 6

Beyond these partnerships, the foundation also launched its flagship program, Max Access Solutions, with a goal of creating a “robust patient program, a network of partner-leading cancer-treating institutions, and a validated end-to-end supply chain into cancer treatment centers to enable safe humanitarian access,” Garcia-Gonzalez and colleagues wrote in a 2018 publication.10

In parallel to Max Access Solutions, the foundation runs the Max Innovation Lab, which “serves as a platform for idea incubation, programmatic design, and implementation.”

The foundation also works to strengthen health systems through core programming that improves diagnostic capacity, patient advocacy, clinical education, support care, and disease management. The foundation’s global team provides patients with psychosocial support, transportation assistance, adherence monitoring, and other services.

Supporting The Max Foundation

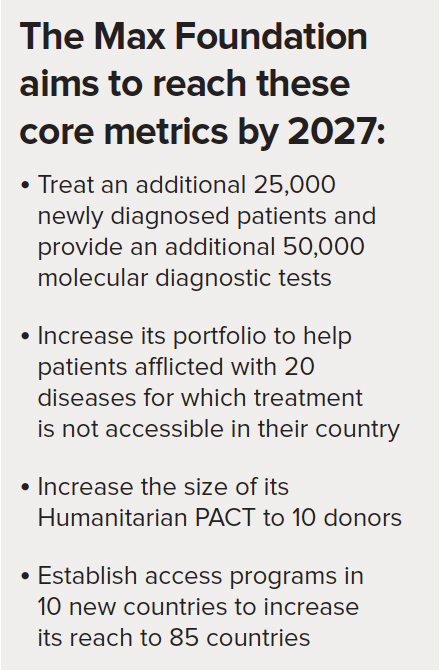

As the foundation continues to grow and evolve, its five-year strategic plan includes goals to expand geographically and double the number of new patients supported, diseases treated, and donors in the Humanitarian PACT.

For those who want to support The Max Foundation’s goals, there are many ways hematologic oncologists and other clinicians can get involved, Garcia-Gonzalez said.

It starts with raising awareness of the foundation’s work and the remaining challenges, she emphasized. For example, when she learned about the lack of diagnostics in Ethiopia, she shared the story widely in an effort to address the issue.

“It was by sharing with everyone that I found solutions,” Garcia-Gonzalez said.

There are several additional ways to help, including volunteering and donating. However, there’s one key area particularly in need of support.

“We still have a huge gap in diagnostics,” she said. “I think [diagnostics are] the best investment you can make, because you help somebody get diagnosed, and then they can have treatment for the rest of their life. I think that’s one of the areas where you can make the biggest impact.”

The foundation is also expanding its impact by joining forces with the WHO, the Union for International Cancer Control, and many other major stakeholders to form the Access to Oncology Medicines Coalition.

“We can take what The Max Foundation has done and replicate it to all cancers in a … broader way, so that all patients with cancer can have access to treatment,” Garcia-Gonzalez said.

As the foundation evolves and expands its reach, the overarching goal remains the same: to honor Max’s memory by creating a world where “geography is not destiny” for patients and families around the world.

Cecilia Brown is an Assistant Editor for Blood Cancers Today.

References

- WHO outlines steps to save 7 million lives from cancer. Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization. February 4, 2020. Accessed March 10, 2023. https://www3.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=15708:who-outlines-steps-to-save-7-million-lives-from-cancer&Itemid=0&lang=en

- Maximiliano M. Rivarola. Friends of Max. January 19, 2008. Accessed March 10, 2023. https://friendsofmax.info/maximiliano-m-rivarola/

- Garcia-Gonzalez P. Remembering Max. The Max Foundation. March 8, 2022. Accessed March 10, 2023. https://themaxfoundation.org/stories/remembering-max/

- Fundytus A, Sengar M, Lombe D, et al. Access to cancer medicines deemed essential by oncologists in 82 countries: an international, cross-sectional survey. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(10):1367-1377. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00463-0

- Iqbal N, Iqbal N. Imatinib: a breakthrough of targeted therapy in cancer. Chemother Res Pract. 2014. doi:10.1155/2014/357027

- 2022-2026 Strategic Plan. The Max Foundation. Accessed November 1, 2022. https://www.themaxfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Max-Strategic-Plan-spreads.pdf

- Owojuyigbe T. A story of hope from a doctor’s perspective. The Max Foundation. October 20, 2022. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://themaxfoundation.org/stories/a-story-of-hope-from-a-doctor-perspective/

- Subramanian S. In India, patient meetings reduce stigma and unite hope. The Max Foundation. January 8, 2020. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://themaxfoundation.org/stories/in-india-patient-meetings-reduce-stigma-and-unite-hope/

- Umeh CA, Garcia-Gonzalez P, Tremblay D, Laing R. The survival of patients enrolled in a global direct-to-patient cancer medicine donation program: the Glivec International Patient Assistance Program (GIPAP). EClinicalMedicine. 2020. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100257

- Garcia-Gonzalez P, Lopes G, Schwartz E, Shulman LN. The role of humanitarian donations in decreasing preventable mortality from cancer in low-income countries: models to improve access to life-saving medicines. J Glob Oncol. 2018;4:1-3. doi:10.1200/JGO.18.00096

© 2025 Mashup Media, LLC, a Formedics Property. All Rights Reserved.

© 2025 Mashup Media, LLC, a Formedics Property. All Rights Reserved.