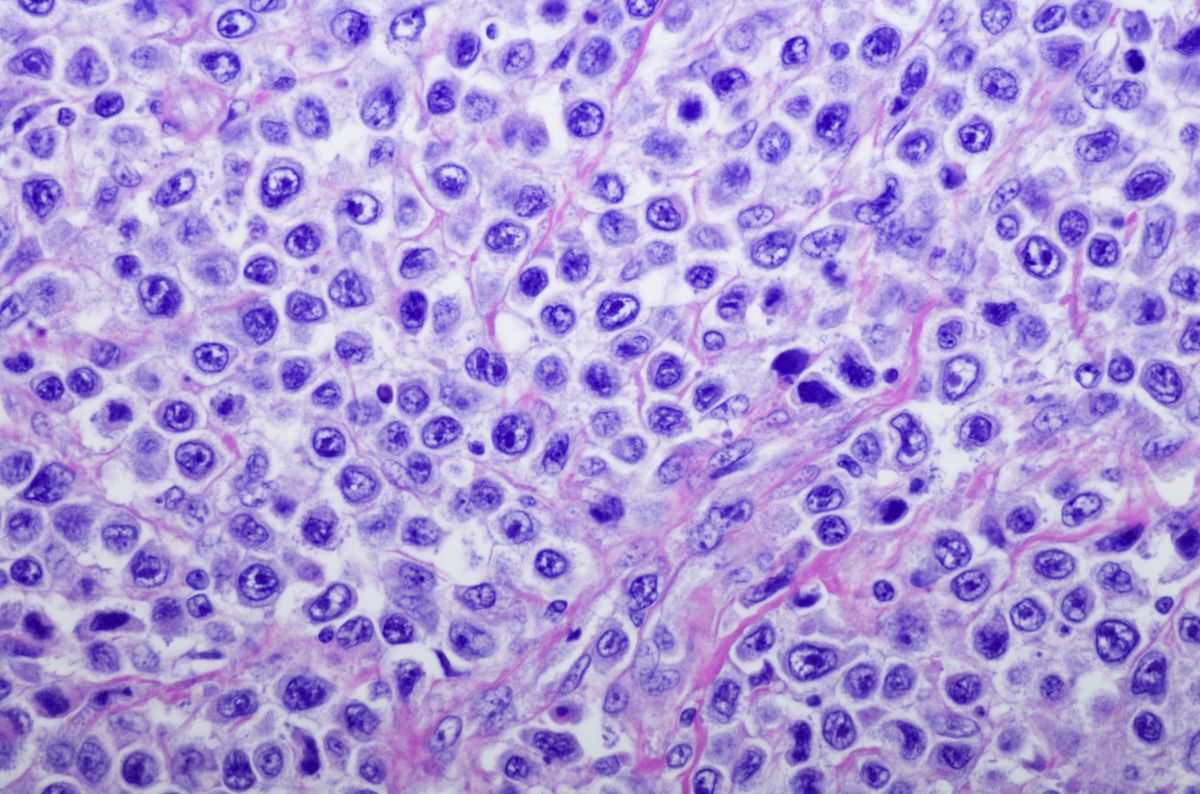

For patients with relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), a new challenge has emerged. Given the multitude of novel therapies recently approved, clinicians must consider how to best sequence the options in individual patients.

After years of limited choices for treatment in the relapsed/refractory setting, the availability of numerous effective novel agents is a welcome dilemma. Historically, autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation represented the primary curative option. Beyond that, management quickly became palliative. Single-agent or multiagent chemotherapy yielded poor outcomes, with few patients achieving durable benefit.

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy targeting CD19 has transformed management for relapsed/refractory disease. It was initially evaluated in patients who had received at least two prior lines of therapy, and results exceeded expectations compared with standard management. With more than five years of follow-up of the initial pivotal trials, it seems fair to conclude that CAR T-cell therapy can be curative in approximately one-third of select patients amenable to treatment. Subsequent phase III trials have also demonstrated improvement in event-free survival in the second-line setting in transplant-eligible high-risk patients with axicabtagene ciloleucel or lisocabtagene maraleucel compared with the standard approach of salvage therapy and transplantation. More recently, safety and efficacy of second-line CAR T-cell therapy has also been demonstrated in transplant-ineligible patients, leading to approvals in this setting. Thus, CAR T-cell therapy has altered the treatment algorithm for relapsed/refractory patients and would be considered a preferred option for approved indications in appropriate patients.

Beyond CAR T-cell therapy, since 2019, four additional novel therapy approaches have been approved for treating relapsed/refractory disease. Available options now include the CD79b-targeted antibody-drug conjugate polatuzumab vedotin combined with bendamustine and rituximab (pola-BR); the XPO1 inhibitor selinexor; the anti-CD19 monoclonal antibody tafasitamab combined with lenalidomide (TAFA-LEN); and, most recently, the antibody-drug conjugate targeting CD19, loncastuximab tesirine-lpyl. Pola-BR approval was based on a randomized, phase II trial in comparison with BR alone, whereas remaining agents were approved based on pivotal phase II data. As such, comparative data among these options are lacking. Cross-trial comparisons cannot easily be made due to variable patient eligibility criteria leading to different patient characteristics. Collectively, overall response rates (ORRs) range from 28% to 58%, with complete remission (CR) rates ranging between 10% and 40%. While some patients have achieved durable benefit, follow-up durations are too short to assess the curative potential of these novel agents.

Considerations for sequencing should take into account overall goals of therapy, assessment of risk and benefit in individual patients based on unique toxicity profiles, and patient preferences. While pola-BR was evaluated in relapsed/refractory patients who had received at least one prior line of therapy, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration indication is for patients following two prior lines (despite broader indication worldwide). In the randomized cohort of the phase II trial, the ORR was 45% (CR rate, 40%), and median progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were 9.2 months and 12.4 months, respectively. Advantages of pola-BR include the fact that it is a finite regimen (intended for six cycles) and is generally well tolerated. Primary toxicities include cytopenia and neuropathy. Due to profound lymphodepletion, bendamustine should be avoided prior to CAR T-cell therapy.

TAFA-LEN, a novel immunotherapy approved for use after one prior line of therapy, has shown durable benefit in patients achieving a CR. In the phase II trial, the ORR was 58% (CR rate, 40%), and median PFS and OS were 11.6 months and 33.5 months, respectively. The treatment does require frequent intravenous infusion of tafasitamab, which continues indefinitely, whereas lenalidomide is limited to a duration of one year. This regimen has been attractive, as it avoids the use of further chemotherapy, but it is not without toxicity, which is largely attributable to lenalidomide. Limited data suggest that CD19 downregulation following tafasitamab is not a major concern, but it should remain a consideration when sequencing prior to CAR T-cell therapy. Of note, the pivotal trial was performed in a favorable patient cohort, as primary refractory patients were initially excluded. A recent real-world analysis suggests this regimen is most effective in patients with relapsed disease following one prior line of therapy.

Selinexor, an oral agent taken twice weekly until progression, has been approved after two lines of prior therapy. In the phase II trial, the ORR was 28% (CR rate, 10%), and median PFS and OS were 2.6 months and not yet reached, respectively. Primary toxicities include constitutional symptoms and fatigue that may impact quality of life. Selinexor offers a convenient schedule of administration, but modest activity has lowered enthusiasm for its use.

Finally, loncastuximab tesirine-lpyl, administered intravenously every three weeks for one year and every three months subsequently, has also been approved following two lines of therapy. In the phase II trial, the ORR was 48% (CR rate, 24%), and median PFS and OS were 4.9 months and 9.9 months, respectively. It is generally well tolerated, with main toxicities including cytopenia and transient transaminitis. Initial reported activity appears modest, but longer follow-up and more data in earlier lines of therapy would help judge its merit. Also, few data are available regarding its use prior to CAR T-cell therapy, which is a consideration based on its CD19 target.

The expected approval of bispecific antibodies in patients who have received at least two prior lines of therapy will likely make management in the relapsed/refractory setting increasingly complex. Bispecific antibodies, such as glofitamab, epcoritamab, and odronextamab, have shown the ability to induce durable remissions following multiple lines of therapy, including CAR T-cell therapy. Based on their reported efficacy and favorable toxicity profile, bispecific antibodies will likely be highly utilized and may be prioritized ahead of several current available options.

The availability of an array of novel therapies in relapsed/refractory DLBCL has undoubtedly improved outcomes. However, more information is required to optimize their use. In view of the biological diversity of DLBCL and the variable resistance mechanisms that may be at play in individual patients, identifying predictive biomarkers is a high priority. Ultimately, the availability of validated biomarkers is essential to move from the current approach of empiric therapy toward precision-based care.

Laurie H. Sehn, MD, MPH, is a Clinical Professor of Medical Oncology at the British Columbia Cancer Centre for Lymphoid Cancer.

© 2025 Mashup Media, LLC, a Formedics Property. All Rights Reserved.

© 2025 Mashup Media, LLC, a Formedics Property. All Rights Reserved.