While recent advances in therapeutics and steady improvements in supportive care for patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) have prolonged survival, even patients who achieve a complete remission with initial therapy have high rates of relapse. To solve this clinical dilemma, investigators have proposed several maintenance therapy strategies to extend remission and overall survival in AML. Strategies range from immunotherapy to targeted therapies to hypomethylating agents. Recently, clinical trials of oral azacitidine have shown promising results, but clinical trials of maintenance therapy in this setting are limited, leaving no definitive answer to the question of whether maintenance therapy is necessary in AML.

At the 2021 SOHO Annual Meeting, Farhad Ravandi, MD, and Jeffrey Lancet, MD, squared off on this clinical quandary, with Dr. Ravandi arguing in favor of maintenance therapy and Dr. Lancet arguing that maintenance strategies have not yet been proven beneficial in this setting.

Maintenance Therapy Is Valuable in AML

Farhad Ravandi, MD

The goal of maintenance therapy is to target and suppress low levels of residual disease after the initial therapy with induction, consolidation, or even allogeneic stem cell transplantation (ASCT). Historically, for maintenance therapy, we have used conventional cytotoxic agents which are associated with significant cytopenias and other off-target toxicity. Fortunately, we now have several effective and relatively non-toxic oral agents that have expanded our horizon in terms of maintenance therapy.

Maintenance therapy has not been as prevalent in AML as in other diseases, owing to several challenges. We need effective and well-tolerated agents that must be evaluated in prospective trials with large patient populations. Enrolling a sufficient number of patients is difficult, as eligible participants must have disease in remission and be ineligible for other strategies such as ASCT. These trials will also need long follow-up, which requires enthusiasm on the part of investigators and patients.

So far, we have had few positive trials in maintenance therapy but, like anything else, there has been an evolution in maintenance therapy of AML over the years.

The Evolution of Maintenance Therapy

Initially, several smaller studies used either conventional cytotoxic agents or immune-based strategies and, of course, few showed any survival benefit. In the mid-2000s, hypomethylating agents (HMAs) such as decitabine and azacitidine proved reasonably effective against myeloid disorders and relatively well tolerated, so several trials evaluated these agents for maintenance therapy in AML.

The trials of HMAs have historically been hampered by low enrollment. In one of the larger randomized trials, ECOG-ACRIN investigators enrolled only 120 older patients with AML and compared 3 days of decitabine versus supportive care alone.1 With some statistical maneuvering, the investigators showed that the decitabine strategy was beneficial, both in terms of disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS). Again, though, the study was hampered by the relatively low number of patients who were randomized. HOVON investigators also randomized patients to receive either azacitidine 50 mg daily for 5 days every 4 weeks for up to 1 year or 12 cycles or observation.2 A total of 116 patients were enrolled and the trial ended early because of slow accrual.

The Promise of CC-486 and Targeted Agents

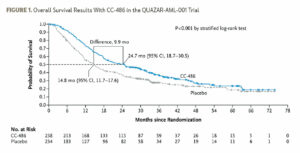

The QUAZAR AML-001 trial is the largest study in maintenance therapy in AML. It studied CC-486, an oral formulation of azacitidine, in patients over the age of 55 who had received initial traditional chemotherapy induction with or without consolidation and were in first remission.3 Eligible participants had de novo or secondary AML with intermediate- or poor-risk cytogenetics, but they must have been ineligible for ASCT. Patients were randomized 1:1 to CC-486 300 mg for 2 weeks every 28 days or placebo. This study was strongly positive, showing an approximately 10-month advantage in OS favoring CC-486 (Figure 1). CC-486 is an active agent so it was associated with some myelosuppression and gastrointestinal toxicity. Notably, though, the study did not mandate antiemetics so prophylactic use of antiemetics could alleviate some of the gastrointestinal toxicity.

The FLT3 inhibitor midostaurin was evaluated in the maintenance portion of the RATIFY trial and, in a German subgroup analysis of a prospective phase II trial in patients with FLT3-ITD positive AML.4 Notably, this trial enrolled a large number of patients—284. They all received midostaurin as induction and consolidation therapy, then proceeded to ASCT followed by maintenance with midostaurin. However, only 34% of the enrolled patients ever started maintenance therapy. When they compared their findings with historic controls, the investigators felt that the addition of midostaurin maintenance was associated with significant improvement in outcomes in both the younger and older subgroups.

Another FLT3 inhibitor, sorafenib was evaluated in the SORMAIN trial of FLT3-ITD positive patients with AML who had undergone ASCT and were in CR at the time of enrollment.5 Participants were randomized 1:1 to sorafenib 400 mg twice daily for up to 2 years or placebo. Again, this trial was small, with only 83 enrolled patients. Investigators were able to show a significant improvement in relapse-free survival with post-ASCT sorafenib.

Investigators are now looking at maintenance with more potent FLT3 inhibitors that are now available, such as gilteritinib and quizartinib. Ongoing trials will hopefully better clarify the role of these agents in maintenance therapy.

Wider Adoption of Maintenance Therapy

Looking at the challenges to adopting maintenance therapy on a wider scale, it appears that we are meeting them. We now have reasonably effective and reasonably well-tolerated oral agents, and several ongoing studies are looking at their potential as maintenance strategies.

So, what is the future of maintenance therapy in AML? Hopefully with the strategies I have discussed, our maintenance strategies will significantly improve. For example, Kadia et al. are embarking on maintenance strategies based on patients’ molecular mutations. Cohort selection is based on mutation analysis, so that patients with FLT3-mutated disease receive CC-486 plus gilteritinib maintenance, patients with IDH2-mutated disease receive CC-486 plus enasidenib maintenance, patients with IDH1-mutated disease receive CC-486 plus ivosidenib maintenance, and patients with no detectable mutations receive CC-486 plus venetoclax maintenance. Hopefully, these strategies will prove effective in reducing relapse risk and improving survival.

We also know that, when we have very effective initial therapy for disease, we actually can abandon maintenance, though. This was the case with APL. For years, the standard strategy was administering 1 or 2 years of all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA) as maintenance after induction with ATRA plus chemotherapy. But, when the ATRA and arsenic trioxide regimen proved highly effective in eradicating residual leukemia, at least in standard-risk patients, it was clear that we did not need maintenance therapy in APL. Perhaps this is going to be the future in AML, where we are developing very effective initial strategies. In the future, we can hope to not need maintenance therapy.

References

- Foran JM, Sun Z, Claxton DF, et al. Maintenance Decitabine (DAC) Improves Disease-Free (DFS) and Overall Survival (OS) after Intensive Therapy for Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) in Older Adults, Particularly in FLT3-ITD-Negative Patients: ECOG-ACRIN (E-A) E2906 Randomized Study. Blood. 2019; 134 (Supplement_1):115.

- Huls G, Chitu DA, Havelange V, et al. Azacitidine maintenance after intensive chemotherapy improves DFS in older AML patients. Blood. 2019;133(13):1457-1464.

- Wei AH, Dohner H, Pocock C, et al. Oral Azacitidine Maintenance Therapy for Acute Myeloid Leukemia in First Remission. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(26):2526-2537.

- Schlenk RF, Weber D, Fiedler W, et al. Midostaurin added to chemotherapy and continued single-agent maintenance therapy in acute myeloid leukemia with FLT3-ITD. Blood. 2019;133(8):840-851.

- Burchert A, Bug G, Fritz LV, et al. Sorafenib Maintenance After Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation for Acute Myeloid Leukemia With FLT3–Internal Tandem Duplication Mutation (SORMAIN). J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(26):2993-3002.

Farhad Ravandi, MD, is the Janiece and Stephen A. Lasher Professor of Medicine and Chief of Section of Developmental Therapeutics in the Department of Leukemia at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas.

Maintenance Therapy in AML Is Not Necessary

Jeffrey Lancet, MD

The current maintenance strategies in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) leave much to be desired, and many ideas need to be explored before maintenance therapy becomes widely accepted and useful.

Before tackling new questions, several basic questions must be considered when weighing the necessity of maintenance therapy: What are the goals of maintenance therapy—prolonging relapse-free survival or converting patients to a measurable residual disease (MRD)–negative state—and how do we determine whether it is successful? Does maintenance therapy’s potential impact on quality of life justify the potential benefits, particularly if these benefits are short-lived? Most importantly, how strong are the data to support maintenance therapy in the current era?

Defining Maintenance Therapy

First, what does “maintenance therapy” even mean? Is it any different from any other form of post-remission therapy?

The National Cancer Institute defines consolidation therapy as “treatment that is given after cancer has disappeared following the initial therapy” and maintenance therapy as “treatment that is given to help keep cancer from coming back after it has disappeared following the initial therapy.” The definitions are eerily similar.

Conceptually, one would expect that maintenance therapy is intended to decrease the number of cancer cells to some plateau level, maybe even to zero, thereby slowing the time to relapse. This definition, though, implies a need for indefinite therapy. Can we identify a threshold of MRD necessary to prevent or delay relapse?

Targeting the True Drivers of Relapse

Research has elucidated the importance of preleukemic mutations in hematopoietic precursor cells in the transformation process, so it stands to reason that eliminating these cells would prevent the progression. However, is that a realistic goal? And, will it matter? We would want to eliminate these cells to prevent the progression, but is that a realistic goal?

I do not think there is a consensus on this, but evidence strongly suggests that the answer to both of those questions is no. The clearance—or lack of clearance—seems to have little impact on the likelihood of relapse. So, if maintenance therapy is geared at removing the founding clone, so to speak, I think it’s safe to say that we’re not very good at doing that yet.

On a similar note, relapse often arises from rare preleukemic hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) or dormant leukemic stem cells (LSCs), so targeting “stemness” or ensuring we hit the mutations in these specific LSCs, rather than acquired mutations that are more specific to the bulk leukemia population.

At this point, I doubt any maintenance strategies have the ability to target stemness itself or the key components of leukemic genetic alterations that ultimately lead to relapse.

Azacitidine and QUAZAR-AML-001

In the past 15 years, there have been precious few randomized trials that could answer the question of the whether maintenance therapy benefits patients.

A randomized trial comparing 1 year of subcutaneous azacitidine with observation in older AML patients found only a modest improvement in disease-free survival (DFS), but no improvement in overall survival (OS).1 Notably, most of the time spent in remission was spent taking maintenance treatment. The lack of OS improvement suggests that patients who are on observation can go on to beneficial therapy, which may offset any benefit of DFS experienced by patients receiving maintenance therapy.

The QUAZAR-AML-001 study finally moved the needle a bit on maintenance therapy in AML.2 The 10-month survival advantage with CC-486 suggested that the chronicity of the drug may be worth it. There are several caveats to explore, though. As with just about everything else in life, one size does not fit all. In QUAZAR-AML-001, patients who were MRD-negative at study entry, who had no prior MDS or CMML, or who had poor-risk cytogenetics seemed to experience a less-significant benefit with CC-486 compared with placebo. Also, only 10% of the study population had secondary AML, which is substantially lower than in a real-world scenario, where up to 40% of patients older than 60 have secondary AML.

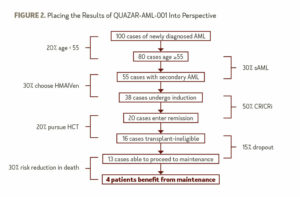

In my opinion, CC-486 is the only drug to date that has shown a clear benefit as maintenance therapy in AML. But, is the potential benefit enough to recommend standard maintenance therapy? To put the results of QUAZAR-AML-001 in perspective, imagine 100 cases of AML (Figure 2).

After removing about 20% of patients who are under age 55, the 30% (conservatively) of patients with secondary AML, and the patients who opt to receive a hypomethylating agent plus venetoclax as an alternative to induction, only about 38 patients who have received induction therapy and would be likely to receive CC-486. Then, assuming a possible complete remission (CR) and CR with incomplete hematologic recovery (CRi) rate of 50% and that 20% of patients are transplant-eligible, only 16 will likely proceed to maintenance therapy as opposed to transplant. Accounting for a 15% dropout rate between the completion of therapy and the time to starting maintenance, only 13 patients are left. We can assume a 30% risk reduction in death, as evidenced by the QUAZAR-AML-001 study, and the grand total of patients who would truly benefit from maintenance therapy, out of the original 100, is 4.

The Future of Maintenance Therapy

Maintenance therapy is a complex topic, and it is unclear what drives potential benefit. To date, I think we have a poor understanding of the effect of maintenance therapy on clonal burden, which potentially increases the duration of therapy and puts patients at risk for toxicity. Only one trial, QUAZAR-AML-001, showed a truly positive outcome with maintenance therapy and current evidence supporting maintenance therapy is limited to restricted patient populations.

We must acknowledge that clinical trial findings may not be applicable to the bulk of leukemia patients. Perhaps more effective therapies that induce an MRD-negative state will abrogate the need for maintenance therapy in the future. But, in its current state, maintenance therapy has a minimal impact on outcomes in AML.

References

- Huls G, Chitu DA, Havelange V, et al. Azacitidine maintenance after intensive chemotherapy improves DFS in older AML patients. Blood. 2019;133(13):1457-1464.

- Wei AH, Dohner H, Pocock C, et al. Oral Azacitidine Maintenance Therapy for Acute Myeloid Leukemia in First Remission. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(26):2526-2537.

Jeffrey Lancet, MD, is Chair of the Department of Malignant Hematology at Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Florida.

© 2025 Mashup Media, LLC, a Formedics Property. All Rights Reserved.

© 2025 Mashup Media, LLC, a Formedics Property. All Rights Reserved.