Clinicians discuss how the two available second-line CARs can be successfully incorporated into the management of large B-cell lymphoma

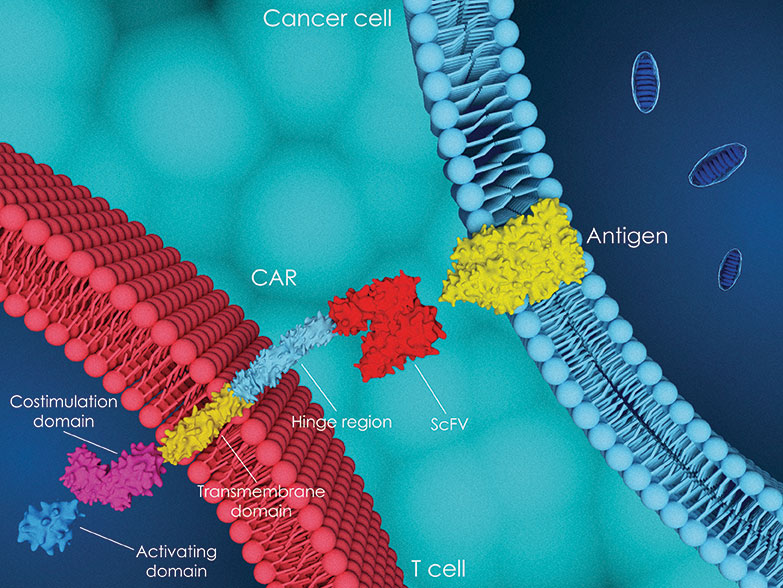

There are now two chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies approved for the second-line treatment of primary refractory or early relapsed large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL): axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel) and lisocabtagene maraleucel (liso-cel).1,2

“We are getting more and more referrals for patients with primary refractory disease or early relapse within 12 months for second-line therapy with CAR T-cell,” said Monalisa Ghosh, MD, Assistant Professor at University of Michigan Health.

This increase in referrals is good because the biggest take-away from trials presenting outcomes for these patients undergoing CAR T-cell therapy is that early referral is crucial.

The standard of care for first-line therapy of LBCL remains R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone).

“Fortunately, many patients will be cured with upfront combination chemotherapy, but some will not,” said Frederick Locke, MD, Chair of the Department of Blood and Marrow Transplant and Cellular Immunotherapy at Moffitt Cancer Center. “There are three scenarios in which a patient should be referred early for CAR T-cell therapy.”

The first scenario is when frontline therapy is not working.

“This can be as simple as the patient getting an interim positron emission tomography (PET) scan after three cycles, and they still have PET-positive disease,” Dr. Locke said. “They wouldn’t yet be eligible for CAR-T but are at high risk for not being cured.”

The second scenario is when the patient has completed frontline therapy but has any amount of residual disease. The third scenario is if the patient relapses within 12 months of completing initial therapy.

Early referral is important for these patients because primary refractory disease or early relapse likely indicate that the cadence of the disease is fast and that it is biologically proliferative.

“If patients are referred early, we can work with these referring providers to get their patients this therapy and, hopefully, send the patients back in great shape,” Dr. Locke said.

Why Refer Early?

When Dr. Locke mentions “sending patients back in great shape,” he is referring to the improved outcomes that this patient population is seeing with CAR T-cell therapy.

The first U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for CAR T-cell therapy in the second-line setting was for axi-cel in April 2022. This approval was based on results of the ZUMA-7 trial.

The randomized, phase III ZUMA-7 trial tested axi-cel against standard of care in patients with LBCL who were refractory to or had relapsed within 12 months of first-line chemoimmunotherapy. Standard of care was two or three cycles of chemo-immunotherapy followed by high-dose chemotherapy with autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (AHSCT) in patients with a response. The two-year event-free survival (EFS) was 41% for axi-cel compared with 16% for standard of care, equating to a 60% improvement in EFS (hazard ratio [HR]=0.40; 95% confidence interval [CI]; 0.31-0.51; P<.001).3

Median EFS was quadrupled to 8.3 months with axi-cel compared with 2.0 months with standard of care, and 83% of patients assigned to axi-cel responded to the therapy, with a complete response (CR) in 65%.

“These data are very compelling in that it shows that if patients go down the route of combination chemotherapy and transplant if they respond, there was about a 16% chance of that plan working with the patient remaining alive and in remission at two years’ follow-up,” said Dr. Locke, who was an investigator on ZUMA-7.

In June 2022, the FDA also approved liso-cel based on results from an interim analysis of the TRANSFORM trial.4,5

TRANSFORM was a phase III trial that randomly assigned patients to liso-cel or standard of care with chemoimmunotherapy followed by high-dose chemotherapy and AHSCT in responders. Here again, EFS was more than quadrupled with liso-cel compared with standard of care (10.1 vs 2.3 months), equating to a 65% improvement in EFS (HR=0.35; 95% CI, 0.23-0.53; P<.0001). At 12 months, 44.5% of patients who received liso-cel were alive and disease-free compared with 23.7% of patients assigned to standard of care.

“These two randomized, controlled studies met the primary endpoint and demonstrated superiority over autotransplant and thus change my standard of care for these high-risk relapsed/refractory DLBCL patients moving forward,” said Manali Kamdar, MD, Associate Professor of Medicine-Hematology at the University of Colorado Medicine and an investigator on TRANSFORM. “It is very hard for me to now offer autologous transplant to this subset of patients with high-risk LBCL.”

Clinical Decision-Making

With two FDA-approved treatment options and no head-to-head trials, clinicians are unable to make treatment decisions based on differences in efficacy between axi-cel and liso-cel, according to Dr. Ghosh. Instead, things like toxicities, patient-reported outcomes, and logistics must weigh into the decision.

Looking at the constructs themselves, axi-cel is a CAR construct with an extracellular portion composed by a svFC domain targeting CD19 and uses a CD28 costimulatory domain. Liso-cel also targets CD19 but has a 4-1BB costimulatory domain and is administered with a sequential CD8 and CD4 component dose.

“This means these two CAR-T therapies will expand at different rates and cause different levels of toxicity,” Dr. Ghosh explained.

Specifically, Dr. Locke explained that liso-cel has a less rapid expansion and proliferation, but the CAR T-cells may survive longer in the patient. In contrast, axi-cel is rapidly proliferative but has higher cytotoxic potential after infusion.

In TRANSFORM, cytokine release syndrome (CRS) was reported in about half of patients but was only grade ≥3 in 1%. Similarly, any-grade neurological events were reported in 12% of patients but were only grade ≥3 in 4%. No grade 4 or 5 CRS or neurologic events occurred.

In ZUMA-7, grade ≥3 CRS occurred in 6% of patients, and grade ≥3 neurologic events occurred in 21% of patients.

In TRANSFORM, 19 patients received liso-cel in the outpatient setting; 13 of these patients were hospitalized after the infusion—10 because of adverse events—but none were admitted to the intensive care unit.

“Liso-cel is more readily useable in an outpatient setting because these toxicities are less likely to occur, and when they do occur, they tend to occur later,” Dr. Locke said. “I may use liso-cel if a patient is older than 75 years or if I am concerned that a patient has certain comorbidities or may end up needing rehab if they have any sort of toxicity.”

Both ZUMA-7 and TRANSFORM also looked at quality of life and patient-reported outcomes and reported improvements compared with standard of care. Treatment with axi-cel compared with standard of care resulted in significant improvements in QLQ-C30 Physical Functioning, Global Health Status/QoL, and EQ-5D-5L visual analog scale at 100 and 150 days.6 Similarly, treatment with liso-cel resulted in improvement in EORTC WLW-C30 cognitive functioning and fatigue.7

Additionally, unlike axi-cel, liso-cel is also approved in patients who are refractory to first-line chemoimmunotherapy or relapse after first-line therapy and are not eligible for AHSCT due to comorbidities or age.

“You can give liso-cel in transplant-ineligible patients regardless of when they relapse,” Dr. Locke said. “You can’t do that with axi-cel.”

This additional indication was based on results from the phase II PILOT study. This single-arm study enrolled patients ineligible for high-dose therapy and AHSCT. In the study, 74 patients underwent leukapheresis, 82% received liso-cel, and 54% achieved CR.8

The manufacturer of liso-cel is making it a bit harder to have to choose between these two therapies, said Michael R. Bishop, MD, Director of the David and Etta Jonas Center for Cellular Therapy at the University of Chicago, when discussing the somewhat limited manufacturing capacity for liso-cel.

“Axi-cel still has the fastest manufacturing time,” Dr. Ghosh agreed. “That is going to be an important consideration if you have a patient who is actively progressing and you can’t give them bridging therapy.”

In TRANSFORM, the median number of days from leukapheresis to product availability was 23 days in the United States. In ZUMA-7, the median time from leukapheresis to product release was 13 days.

“I generally prefer axi-cel, which seems to have a little more manufacturing capacity,” Dr. Locke said. “We can get patients collected and to the manufacturer quicker, but the turnover time once manufacturing begins is usually quicker as well.”

In addition, Dr. Locke said that in his experience, axi-cel is more commonly manufactured to specification.

Lessons from BELINDA

ZUMA-7 and TRANSFORM are often discussed in the same conversation as BELINDA, the phase III trial of tisagenlecleucel (tisa-cel) in LBCL that showed that the CAR T-cell therapy was not superior to standard salvage therapy.9

“We are coming up on about a year from when I shared first results,” said Dr. Bishop, who was an investigator on BELINDA. “As the investigators, we were in shock. Novartis was in shock. We had been working to get the trial done so we could get the results out and get this product to patients.”

Dr. Bishop said he still spends time considering why the trial may not have been successful. However, Dr. Ghosh said that she was not necessarily surprised that the trial was negative, given some of the differences in trial design.

These differences include how EFS was defined, conditioning regimens given, and permittance of bridging chemotherapy. Another important difference was the time from leukapheresis to infusion of CAR T-cells, which was a median of 52 days in BELINDA.

“I think it was mainly trial design that affected the results,” Dr. Ghosh said. “Some people may perceive that tisa-cel may be less effective than other CAR-Ts, but I have had several patients who responded well to tisa-cel and remained in remission for several years.”

Dr. Locke also said that he has treated patients with LBCL with tisa-cel with good success.

“Even recently, we have used it when we needed to, but it is likely to be favored less and less in LBCL,” Dr. Locke said.

Dr. Bishop agreed, “In 2022, I can’t say there is a role for tisa-cel for patients who relapse within 12 months with aggressive LBCL.”

Barriers to Care

Despite now having two FDA-approved therapies available for second-line use in patients with refractory or early relapsed disease, some barriers to treatment still exist, the experts said.

“It is important that there is increased awareness of these treatments in the community,” Dr. Kamdar said. “We know that community oncologists have busy practices. When they see patients who meet these criteria, it will be very important to get in touch with a CAR T-cell therapy center right away.”

This early referral allows these centers to begin to tackle other barriers, which can include insurance approvals and manufacturing logistics. Patients can come in for a biopsy to confirm disease progression and begin to secure a date for apheresis.

“Manufacturing slots are assigned by the company, and we have to have resources set up to perform apheresis on a particular date,” Dr. Kamdar said. “We don’t want to be held up waiting on insurance.”

Another major barrier is cost, Dr. Ghosh said.

“The expense of this therapy is significant,” Dr. Ghosh said. “This is especially true for patients who have Medicare or Medicaid and may be responsible for some portion of the drug.”

Estimated cost of acquisition of axi-cel or liso-cel is around $400,000, and that does not include infusion-related costs, cost of leukapheresis, bridging corticosteroids, and conditioning chemotherapy.10

Finally, the toxicities of this treatment are still a barrier for certain patients. “There is still significant morbidity and mortality from toxicities,” Dr. Ghosh said. “That means a lot of patients are treated and observed in the inpatient setting, and that can be a significant barrier.”

Post-CAR T-Cell Therapy

There is no FDA-approved drug specifically for the treatment of relapsed or refractory disease post-CAR T-cell therapy.

“Post-CAR T-cell failure is now a new unmet need in the field,” Dr. Kamdar said. “What we usually recommend is repeat biopsy at progression post-CAR T-cell therapy to see if the tumor is still CD19-positive or if it has lost CD19.”

If it is still CD19-positive, a repeated CAR-T infusion may lead to responses. Use of other CD19-directed agents such as tafasitamab in combination with lenalidomide may be worth exploring, Dr. Kamdar said. Another possible regimen is the CD79-directed antibody-drug conjugate polatuzumab vedotin with or without bendamustine and rituximab.11,12

For many patients, the best next bet will be cytotoxic chemotherapy and AHSCT for those achieving remission, Dr. Bishop said.

“I would still investigate if the patient has chemotherapy-sensitive disease, and if so, I would take them to transplant,” Dr. Bishop said. “Allogeneic transplant can even be curative in patients who have disease that is not fully chemotherapy-sensitive.”

Bispecific antibodies such as glofitamab—which targets CD20xCD3—are also showing potential in this patient population. One recent small study of patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse LBCL after CAR T-cell therapy yielded an overall response rate of 67%, with four of nine patients achieving a CR and two a partial response.13 Other bispecific antibodies targeting CD20×CD3 being explored include mosunetuzumab, odronextamab, and epcoritamab.

“We have seen some impressive responses in which bispecific T-cell engagers are reengaging and reactivating the CAR T-cells that are still there,” Dr. Ghosh said.

In patients who experience early CAR T-cell failure due to T-cell exhaustion, the anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitors nivolumab or pembrolizumab may be options for a percentage of patients. One study treated 12 patients who relapsed or were refractory after CAR T-cell therapy with pembrolizumab 200 mg intravenously every three weeks and showed a response rate of 25%.14

If patients become CD19-negative, trials are looking at the idea of bispecific CAR T-cells, which target two antigens instead of one, Dr. Kamdar said. “The idea is very promising, but we need to see if it translates into clinical outcomes that look better,” Dr. Kamdar said.

Research and clinical trials are going to be key to advancing the science and helping to find the best third-line treatment for these patients.

Future Work

Dr. Bishop said he is very happy with the positive results seen with the ZUMA-7 and the TRANSFORM trials but that the field should not be satisfied with a less than 50% response.

“The challenge is that when you know you have something that works as much as this does, is it ethical to try to get patients on clinical trials to try to improve on those results? Are you blowing a patient’s chance at response if you take them to clinical trial?” Dr. Bishop said. “It has made additional research difficult, and there are camps with strong opinions either way.”

More work is going to be needed to explore the ins and outs of that decision, as well as to tease out which patients are the most appropriate candidates for CAR T-cell therapy.

“We thought that CAR T-cells were agnostic to the tumor, but I do believe biology plays a role,” Dr. Bishop said. “Be it the biology of the tumor or the biology of the T-cell, which are often interconnected. We are starting to get a flavor of that, which will lead to further improvement in the CAR T-cell field.”

Leah Lawrence is a freelance health writer and editor based in Delaware.

References

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves axicabtagene ciloleucel for second-line treatment of large B-cell lymphoma. April 1, 2022. Accessed August 12, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-axicabtagene-ciloleucel-second-line-treatment-large-b-cell-lymphoma

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves lisocabtagene maraleucel for second-line treatment of large B-cell lymphoma. June 27, 2022. Accessed August 12, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-lisocabtagene-maraleucel-second-line-treatment-large-b-cell-lymphoma

- Locke FL, Miklos DB, Jacobson CA, et al. Axicabtagene ciloleucel as second-line therapy for large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(7):640-654.

- Kamdar M, Solomon SR, Arnason JE, et al. Lisocabtagene maraleucel (liso-cel), a CD19-directed chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy, versus standard of care (SOC) with salvage chemotherapy (CT) followed by autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) as second-line (2L) treatment in patients (pts) with relapsed or refractory (r/r) large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL): results from the randomized phase 3 TRANSFORM study. Abstract #91. Presented at the 2021 American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting. December 11, 2021.

- Kamdar M, Solomon SR, Arnason J, et al. Lisocabtagene maraleucel versus standard of care with salvage chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation as second-line treatment in patients with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma (TRANSFORM): results from an interim analysis of an open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2022. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00662-6

- Elsawy M, Chavez JC, Avivi I, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in ZUMA-7, a phase 3 study of axicabtagene ciloleucel in second-line large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2022. doi:10.1182/blood.2022015478

- Abramson JS, Solomon SR, Arnason JE, et al. 3845 Improved quality of life (QOL) with lisocabtagene maraleucel (liso-cel), a CD19-directed chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy, compared with standard of care (SOC) as second-line (2L) treatment in patients (pts) with relapsed or refractory (R/R) large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL): results from the phase 3 transform study. Paper presented at: 2021 ASH Annual Meeting and Exposition; December 11-14, 2021; Atlanta, GA. Abstract 3845

- Sehgal A, Hoda D, Riedell P, et al. Lisocabtagene maraleucel (liso-cel) as second-line (2L) therapy for R/R large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL) in patients (pt) not intended for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT): Primary analysis from the phase 2 PILOT study. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(suppl 16):7062. doi:10.1200/JCO.2022.40.16_suppl.7062

- Bishop MR, Dickinson M, Purtill D, et al. Second-line tisagenlecleucel or standard care in aggressive B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(7):629-639.

- Perales M-A, Kuruvilla J, Snider JT, et al. The cost-effectiveness of axicabtagene ciloleucel as second-line therapy in patients with large B-cell lymphoma in the United States: an economic evaluation of the ZUMA-7 trial. Transplant Cell Ther. 2022. doi:10.1016/j.jtct.2022.08.010

- Chong EA, Alanio C, Svoboda J, et al. Pembrolizumab for B-cell lymphomas relapsing after or refractory to CD19-directed CAR T-cell therapy. Blood. 2022;139(7):1026-1038.

- Sehn LH, Herrera AF, Flowers CR, et al. Polatuzumab vedotin in relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(2):155-165.

- Rentsch V, Seipel K, Banz Y, et al. Glofitamab treatment in relapsed or refractory DLBCL after CAR T-cell therapy. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(10):2516.

- Liebers N, Duell J, Fitzgerald D, et al. Polatuzumab vedotin as a salvage and bridging treatment in relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphomas. Blood Adv. 2021;5(13):2707-2716.

© 2025 Mashup Media, LLC, a Formedics Property. All Rights Reserved.

© 2025 Mashup Media, LLC, a Formedics Property. All Rights Reserved.