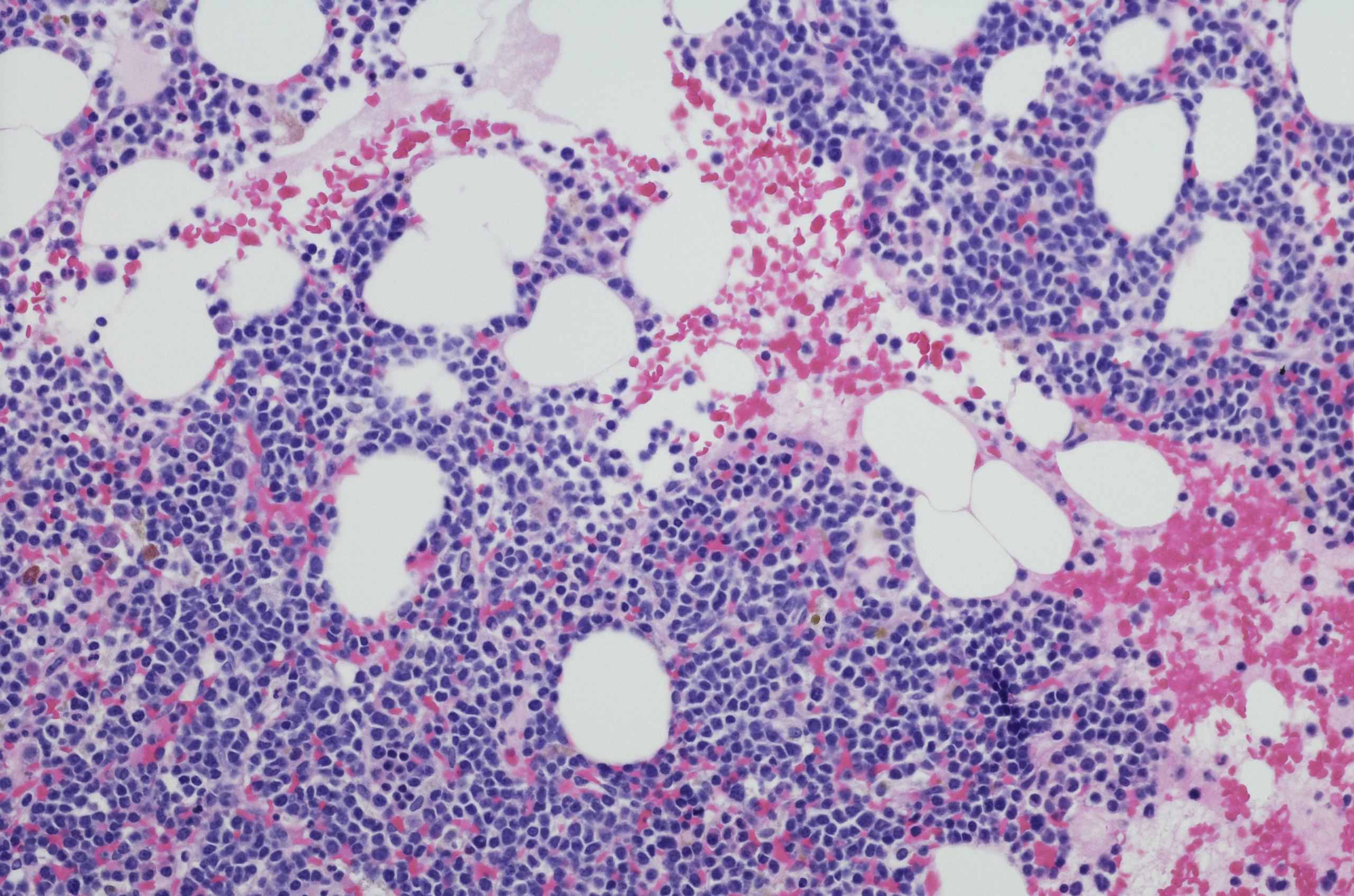

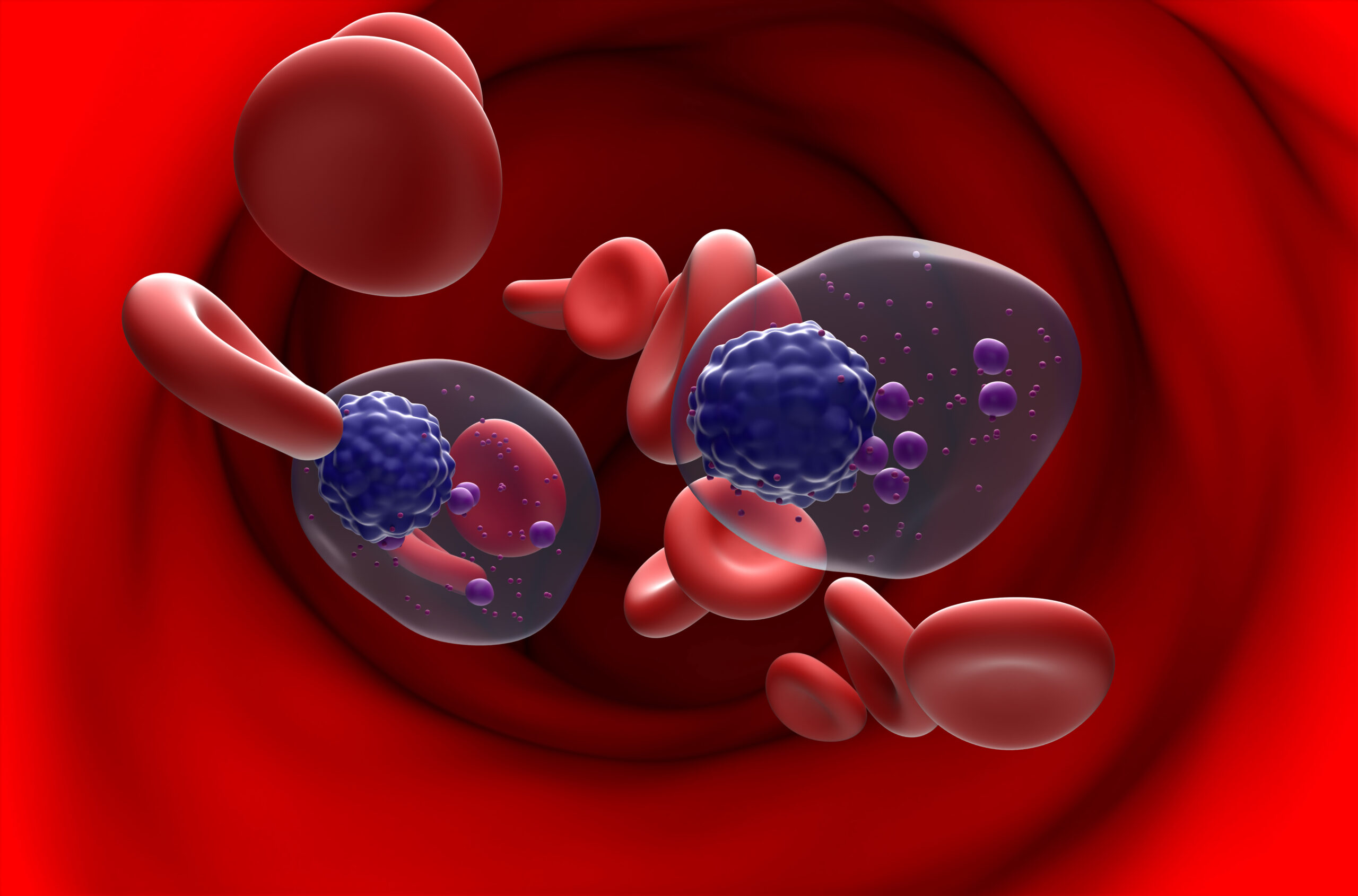

Among patients diagnosed with multiple myeloma (MM) each year, nearly 64% are aged 65 years or older, and this faction accounts for nearly 80% of MM-related deaths. Frailty scales have been developed to aid treatment decision-making in this older patient population.

In this review article, the authors discussed a framework for incorporating frailty scales into clinical care and provided a case vignette that demonstrates the real-world challenges of managing older, frail adults with newly diagnosed MM.

Case Vignette

A 72-year-old woman underwent evaluation for worsening fatigue and shortness of breath, as well as severe back pain that significantly impaired her mobility and was not relieved with acetaminophen. Her Karnofsky performance status was 70%, and lab results confirmed a diagnosis of Revised International Staging System (ISS) III immunoglobulin G kappa MM with high-risk cytogenetics [(t 4;14) and del17p/TP53 mutation]. The patient was concerned about treatment-related adverse events and frequent physician visits. She stated that she was willing to consider non–clinical trial treatment options that can be given closer to home, as she lives alone in a rural community with one adult child who lives out of state. She also stressed the importance of maintaining her independence, mobility, and quality of life.

Using Frailty Scales to Evaluate Patient Fitness

Previous studies have shown that performance status on its own is incapable of fully capturing fitness level in older adults. The ISS can provide disease-related prognostic information but cannot fully detect subgroups that may be at greater risk for treatment-related toxicity and early discontinuations.

To better account for heterogeneity in the aging population, the International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) proposed a frailty score to predict treatment-related toxicity, tolerability, and survival using age, the Katz activities of daily living (ADL), Lawton instrumental ADL, and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI). The patient in the case vignette was determined to be frail based on an IMWG frailty score of 3.

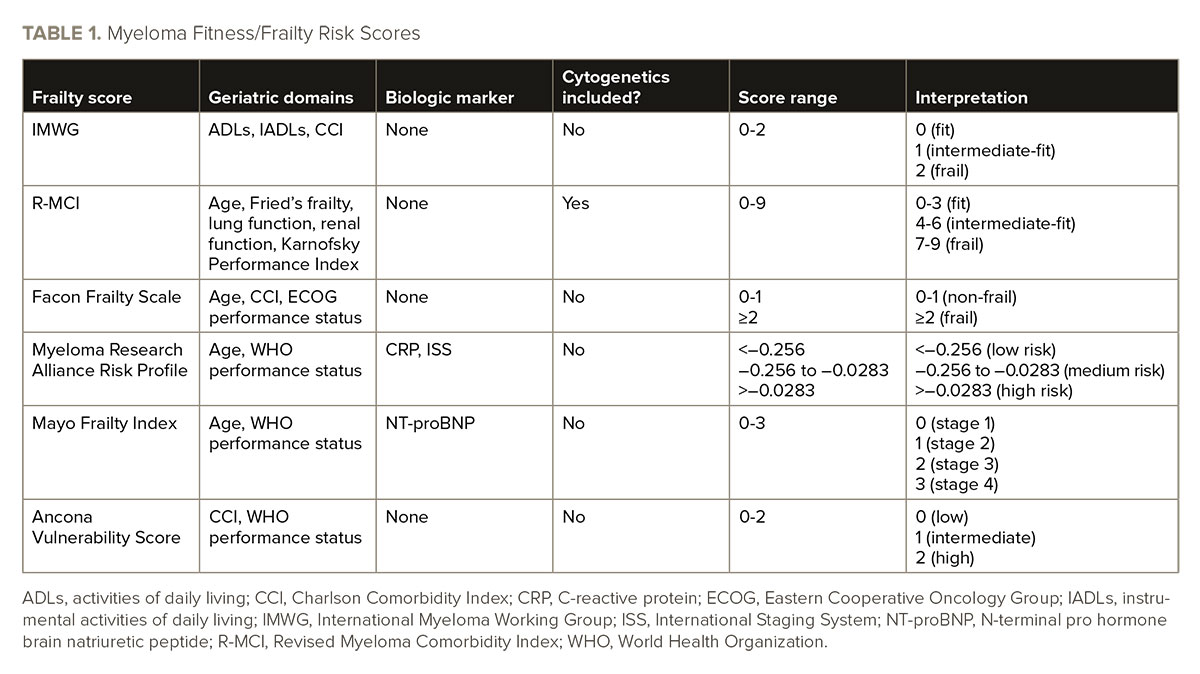

Following the introduction of the IMWG frailty score, attempts have been made to prospectively and retrospectively develop frailty scores in MM that incorporate age, comorbidities, physical performance, and biomarkers (see TABLE 1). Both the IMWG and Facon Frailty Scale were derived from patient data from clinical trials, thus the real-world generalizability of these scoring systems has been questioned.

The gold-standard approach for the global assessment of health status in older adults is the comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA); however, the CGA is a multidisciplinary diagnostic and treatment process that requires time, expertise, and potential specialized testing such as gait speed assessments that are not possible in all settings. CGA is also not routinely implemented in daily practice, so abbreviated tools that can determine who is at greatest risk for poor health outcomes would be beneficial.

Current frailty scores in newly diagnosed MM have been validated with endpoints such as overall and progression-free survival; however, other endpoints that place greater importance on outcomes such as quality of life may be more relevant in this population. The consideration of alternative endpoints would move further toward personalized treatment approaches to ensure that therapies chosen align with the patient’s priorities.

The IMWG frailty score is most commonly used but is limited by its use of chronologic age rather than biologic/functional age. The CCI also likely excludes myeloma-specific comorbidities. Thus, additional work is needed to refine these scores to include cognitive function, disease biology, biomarkers of aging, patient priorities and preference of care, quality of life, and overall life expectancy.

Ultimately, frailty scores are intended to be feasible, be brief, and include assessments that rely on data that patients can self-report or are already captured routinely in electronic health records. A study that assessed the practicability of geriatric assessments in MM found that it took an average of 3.2 minutes for physicians to review the score and resulted in a change in therapy recommendations in 40% of patients, suggesting that incorporating geriatric assessments is useful and feasible.

Frailty assessments should take place throughout the course of treatment to help guide MM treatment intensity based on patient fitness and frailty. Although there is no existing data on the exact interval of reassessing frailty, a time frame of every three to four months could be a reasonable approach to assess the effect of treatment on fitness and frailty and to shape clinical decision-making regarding treatment intensity. Because the patient in the case vignette expressed concerns about treatment-related adverse events, reassessment of the patient’s fitness status during the course of therapy would help balance therapeutic efficacy and safety/tolerability.

Considering a Course of Treatment

For frail patients with newly diagnosed MM, autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (AHCT) is not often feasible due to treatment-related toxicities and tolerability. Disease biology and risk also need to be considered when determining treatment options for this patient population. For the patient in the case vignette, the triplet regimen daratumumab, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone would be optimal based on clinical trial data. Combination therapy with a proteasome inhibitor may also be considered. The patient also mentioned travel-related barriers, so the quadruplet therapy daratumumab, bortezomib, melphalan, and prednisone may be considered.

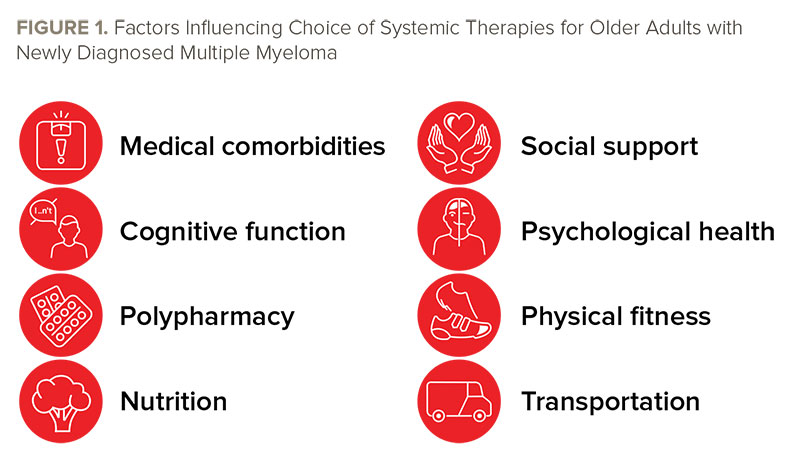

In general, the management of frail older adults should be personalized to account for disease biology, treatment toxicity profile, patient priorities, and preferences for care. See Figure 1 for treatment considerations in this patient population. In addition, comorbidities may impact treatment options in this population. Although there are several frailty scales available, an optimal scale for use in MM has not yet been established.

Geriatric care principles should be guided by solid evidence and a care team that can provide support and interventions for identified vulnerabilities in an effort to advance geriatric oncology by improving clinical outcomes for this older patient population.

© 2025 Mashup Media, LLC, a Formedics Property. All Rights Reserved.

© 2025 Mashup Media, LLC, a Formedics Property. All Rights Reserved.