Tycel Phillips, MD, of the City of Hope, presented on the role of Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors in frontline mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) therapy at the International Ultmann Chicago Lymphoma Symposium (IUCLS) in Chicago, Illinois, on Saturday, April 5. Dr. Phillips joined Blood Cancers Today after the conference to discuss insights from the TRIANGLE and ECHO studies, the implications of pushing BTK inhibitors into the frontline space, and unsolved questions regarding this class of drugs.

What is the current role of BTK inhibitors in frontline therapy in MCL?

During this presentation, we reviewed the natural history of treatment with mantle cell lymphoma, some of the discordance, how we manage patients who are considered young versus older, and the consequences of high-dose chemotherapy preventing these drugs from being used in older patients, given that there’s been a push to move BTK inhibitors into the frontline space. This is especially important, given the efficacy of these drugs in the relapsed or refractory setting, especially second-line therapy. Ideally, we discussed the initial combination of regimens using chemotherapy post BTK inhibitors, starting with the SHINE study.

This study looked at bendamustine-rituximab plus ibrutinib versus bendamustine-rituximab in patients 65 and older with untreated mantle cell lymphoma. This study did meet its primary end point, which was a progression-free survival benefit, but we did see increased toxicity. This did manifest itself in an unclinical trial, which had several unexplained deaths in the experimental arm, which negated any overall survival benefit of the experimental arm and subsequently led to withdrawal of ibrutinib from the United States treatment landscape.

Additionally, a fundamental point is whether a combination is better than sequential, and it appeared that the progression-free survival benefit that we saw with the combination was very close to what we expected when we gave bendamustine followed by second-line therapy with a BTK inhibitor.

Thereafter, we had a more recent clinical trial called the ECHO study, which utilized the second- generation BTK inhibitor acalabrutinib. This BTK inhibitor has less all-target side effects, so it’s more fateful to the BTK receptor and thought to be more tolerable in patients with mantle cell lymphoma.

This study again randomized patients to bendamustine-rituximab as a standard-of-care arm versus bendamustine-rituximab plus acalabrutinib. This study did allow crossover for patients who progressed on the standard-of-care arm, which is bendamustine-rituximab. This study also indicated a progression-free survival [PFS] benefit, albeit the extent of the PFS benefit was not what we saw in the SHINE study.

There were no unexpected deaths in any experimental arm, yet there was still no true, statistically significant overall survival benefit. This has led to FDA approval of the ECHO regimen in patients with mantle cell lymphoma, but fundamentally, it did not necessarily solve the question of whether giving this as a combination is better than giving it sequentially.

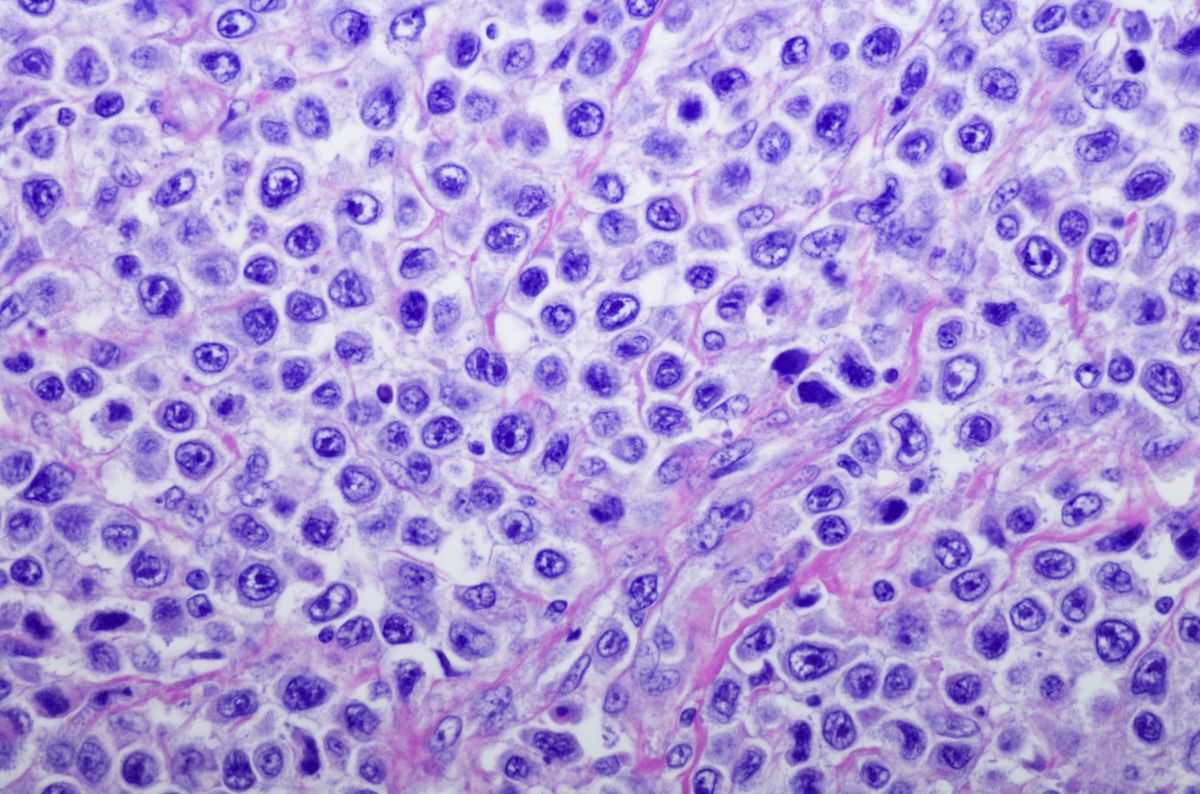

In that context, we do know there are certain high-risk patient populations who would not benefit from chemoimmunotherapy. As such, the addition of acalabrutinib is likely to benefit those patient populations, specifically those with P53 mutations and possibly those with blastoid pleomorphic variants. Ideally, as we get more information from the ECHO trial, we can see how these subsets fared long term.

Next, we turned our attention to the ENRICH study, which did not use chemotherapy but evaluated ibrutinib plus rituximab alone. This was a UK study versus bendamustine-rituximab or R-CHOP [rituximab-cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone]. This trial demonstrated that ibrutinib plus rituximab was better than R-CHOP, but it appears very much equivalent to bendamustine-rituximab in this patient population, with some subtle differences.

Patients with P53 mutations did better with ibrutinib plus rituximab. Patients with the blastoid pleomorphic variant tended to do better in the chemotherapy arm. This supports what we’ve seen with single-agent BTK inhibitors, where patients with blastoid pleomorphic variants don’t have very durable responses.

As a takeaway from these 3 studies in patients who are considered to be unfit or older, meaning 65 and above, combination therapies are effective and appear to be better than chemotherapy alone, but not necessarily better than chemotherapy followed by a BTK inhibitor in the second-line space. In certain patient populations, using BTK inhibitors by themselves appears to be better than chemotherapy, especially in patients with P53 mutations.

Turning our attention to younger patients, the TRIANGLE study was a randomized phase 3 trial that came out of Germany. This randomized patients to the standard-of-care arm, which is R-CHOP alternating with R-DHAP [rituximab, dexamethasone, cytarabine, cisplatin] every other cycle for 6 cycles followed by autologous stem cell transplant. In this situation, the 2 experimental arms were R-CHOP plus ibrutinib alternating with R-DHAP followed by autologous stem cell transplantation and ibrutinib maintenance, or R-CHOP plus ibrutinib alternating with R-DHAP and then ibrutinib maintenance.

When the study was conducted, the 2 experimental arms had ibrutinib maintenance, and the standard-of-care arm had no maintenance therapy. About halfway through the study enrollment, we had the LyMa study readout, which indicated an overall survival benefit to rituximab maintenance after stem cell transplantation. Rituximab was then added to the maintenance arms after all 3 other arms in countries that had an approval for rituximab maintenance.

All patients in the experimental arm had ibrutinib maintenance. Short-term follow-up showed an improved failure-free survival benefit for the 2 experimental arms, suggesting that adding ibrutinib was beneficial in this patient population. It did not appear that there was any substantial benefit to the addition of autologous stem cell transplantation when you add ibrutinib maintenance.

In this younger patient population, it appears that there is some benefit to ibrutinib induction and maintenance. The million-dollar question is: what happens next, given that ibrutinib in the study was only given for 2 years for maintenance? Can we re-treat patients who relapse? This is not a curative treatment.

Moving forward, the question of whether BTK inhibitors could be firmly established in the frontline space is a not a definitive yes or no. There is a benefit to using BTK inhibitors in the frontline space in certain patient populations, but it may not be something we have to utilize for our patients, given that there are consequences of using these drugs up front, and it does impact what we can do in the second-line space, given the inferiority of other standard-of-care regimens in a post-BTK space.

What are the biggest challenges of treating patients with BTK inhibitors?

The biggest challenge is what we do next. If mantle cell lymphoma were curable, then this wouldn’t be a point at all. You use your best guns up front to cure the patient. But we know the cancer is going to come back, and we do know how effective BTK inhibitors can be in a second-line space. What does this mean for us later when these patients eventually relapse, if we cannot use these drugs?

Currently, we don’t have a lot of effective options post BTK therapy other than chimeric antigen receptor [CAR] therapy, and not all patients can get to CAR T-cell therapy. There are some significant side effects to CAR T-cell therapy. If that is our only recourse if we do move up BTK inhibitors in the frontline space, that does limit the push to use these drugs earlier if we’re not necessarily making patients live longer.

The question with TRIANGLE is: if we exclude high-risk patients, do standard- and low-risk patients still get the same overall survival benefit? If they don’t, and if their failure-free survival and progression-free survival aren’t any different than what we would do by breaking up these treatments, that calls into question whether we actually need to use BTK inhibitors in all patients in the frontline space.

Until that is answered, for younger patients, the TRIANGLE approach is very much acceptable, given the overall survival benefit and the opaqueness of the subset analysis. For older patients, I don’t think we have that same push. There is no overall survival benefit in any of these studies. So, you can be very selective when you use a BTK inhibitor for older patients and reserve some of them for later.

Overall, the biggest challenge is what happens next. Until we can firmly answer that question, there always will be a little bit of concern about pushing BTK inhibitors completely into the frontline space.

Read more: Tycel Phillips, MD, on Practice-Changing Studies in MCL

© 2025 Mashup Media, LLC, a Formedics Property. All Rights Reserved.

© 2025 Mashup Media, LLC, a Formedics Property. All Rights Reserved.