Martin Dreyling, MD, a professor of medicine and head of the lymphoma program at the University Hospital LMU Munich in Germany, shares practice-changing developments in mantle cell lymphoma (MCL).

First, Dr. Dreyling explained how MCL is following in the footsteps of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) by drifting from chemotherapy-based regimens.

He also discussed data from the TRIANGLE study presented at the 66th American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting & Exposition. The results confirmed the superiority of ibrutinib plus standard treatment without autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) to autologous HSCT-containing treatment without ibrutinib. The 3-year overall survival was prolonged from 85% in the standard treatment arm to 90% in the ibrutinib plus standard treatment and autologous HSCT arm and to 91% in the ibrutinib without autologous HSCT arm.

What are you most excited about in MCL research?

This is an era of change, and we started decades ago with a disease where we could hardly sufficiently treat patients. We had some chemotherapy-based improvement. At that time, autologous transplant played an important role. Now, we have solid data that we can cut down chemotherapy—it’s efficient, but also toxic—and supplement or substitute with a targeted treatment.

It’s exciting; we are somewhat following the pathway of CLL, where this has already taken place. The only difference is that MCL is seen as an aggressive lymphoma, and therefore this is the first aggressive lymphoma subtype where we say farewell to chemotherapy.

Can you please describe the TRIANGLE study and the role of autologous stem cell transplant in MCL?

We have established the approach of autologous transplant in MCL around about 20 years ago. However, it took 15 years to prove that it’s also improving overall survival, which is the most important point for our patients. That was just 5 years ago. Now, when you apply these targeted approaches in the first-line setting, you push autologous transplant away again. That is what we did in the European trial. Incorporating almost 900 patients, this was a head-to-head comparison of chemo plus autologous transplant or chemo plus targeted, which is in that setting is BTK [Bruton tyrosine kinase] inhibitors, the most active compound in relapsed MCL.

It was a little bit surprising that ibrutinib was not only better tolerated, but it also achieved higher rates of remission, better progression-free survival, and—even more striking now after a follow-up of 5 years—significantly improved overall survival. We are not talking about some borderline tendency, but a 10% increase after a couple of years, which is a major shift. Therefore, this became standard of care in a lot of European countries since 2023.

It’s important to mention that the TRIANGLE trial is really practice-changing and important. This is an academic initiative, so this is a collaboration of national study groups all over Europe. We recruited in 14 different countries, and I think it’s always good that the experts sit together and say how to improve the outcomes of patients. This study is now being submitted to the authorities to apply for an official label for ibrutinib in first-line MCL. That really illustrates how powerful these academic, independent studies are.

You were also involved in a study on p16 as a prognostic marker alone or in combination with p53 abnormalities in young MCL patients. Can you please describe this study?

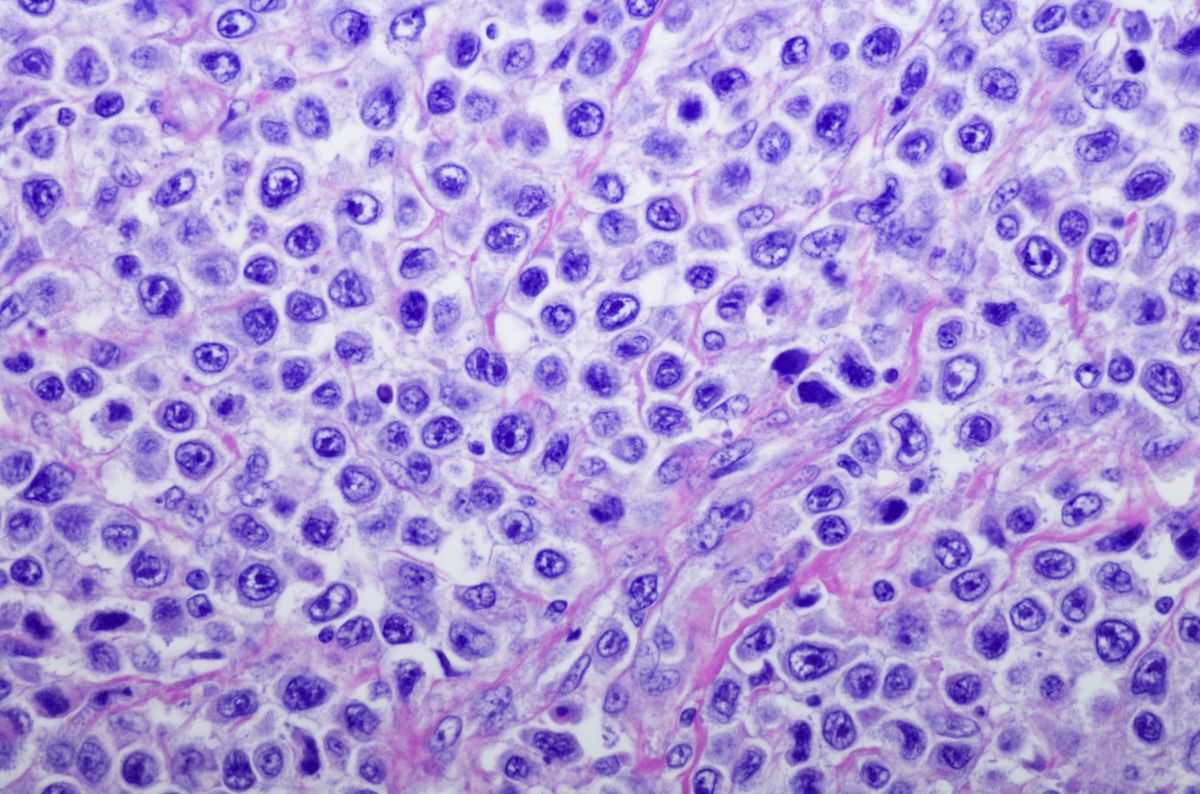

It’s not very new data. We had our first publications on that in the early 1990s, where we explored that at the University of Chicago. But, it takes quite a while to get it implemented to routine clinics. It’s fair to say that if we are considering a risk-adapted treatment in MCL, we are not thinking about clinical parameters like stage or patient age that much. We’re more and more thinking about biological risk factors. These biological risk factors include cytomorphology, blastoids, or more aggressive cytology, and that’s reflected 1 by 1 by cell proliferation, measured by Ki-67. When it comes to the molecular origin of these biological effects, it’s on firsthand p53, and we have also seen that with p16 in an interaction with p53.

In our current lymphoma classifications, detection of p53 alterations is standard of care, even before first-line treatment of MCL. If I do look into the future, I think p16 will be a really important part of this. Five years from now, I think it’s not only p53 anymore, but p53 plus p16, if not additional molecular alterations.

What are the current unmet needs in MCL? What should clinical trials focus on next?

We did the first step of cutting down chemotherapy. In the TRIANGLE trial—and the same holds for a parallel study in elderly patients, which is the ECHO trial of BR [bendamustine and rituximab] plus or minus acalabrutinib—chemo is still in. The next logical question is, “Do we really need chemo at all?” These randomized studies are going on.

We are in an era of change. I think these non-cytostatic combinations have very good chances to compete and to overcome chemotherapy 5 years from now.

Reference

Dreyling M, Doorduijn JK, Gine E, et al. Role of autologous stem cell transplantation in the context of ibrutinib-containing first-line treatment in younger patients with mantle cell lymphoma: results from the randomized Triangle trial by the European MCL network. Abstract 240 presented at: 66th American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting & Exposition; December 7-10, 2024; San Diego, California.

© 2025 Mashup Media, LLC, a Formedics Property. All Rights Reserved.

© 2025 Mashup Media, LLC, a Formedics Property. All Rights Reserved.