The Future of CAR T-Cell Therapy in Lymphoma

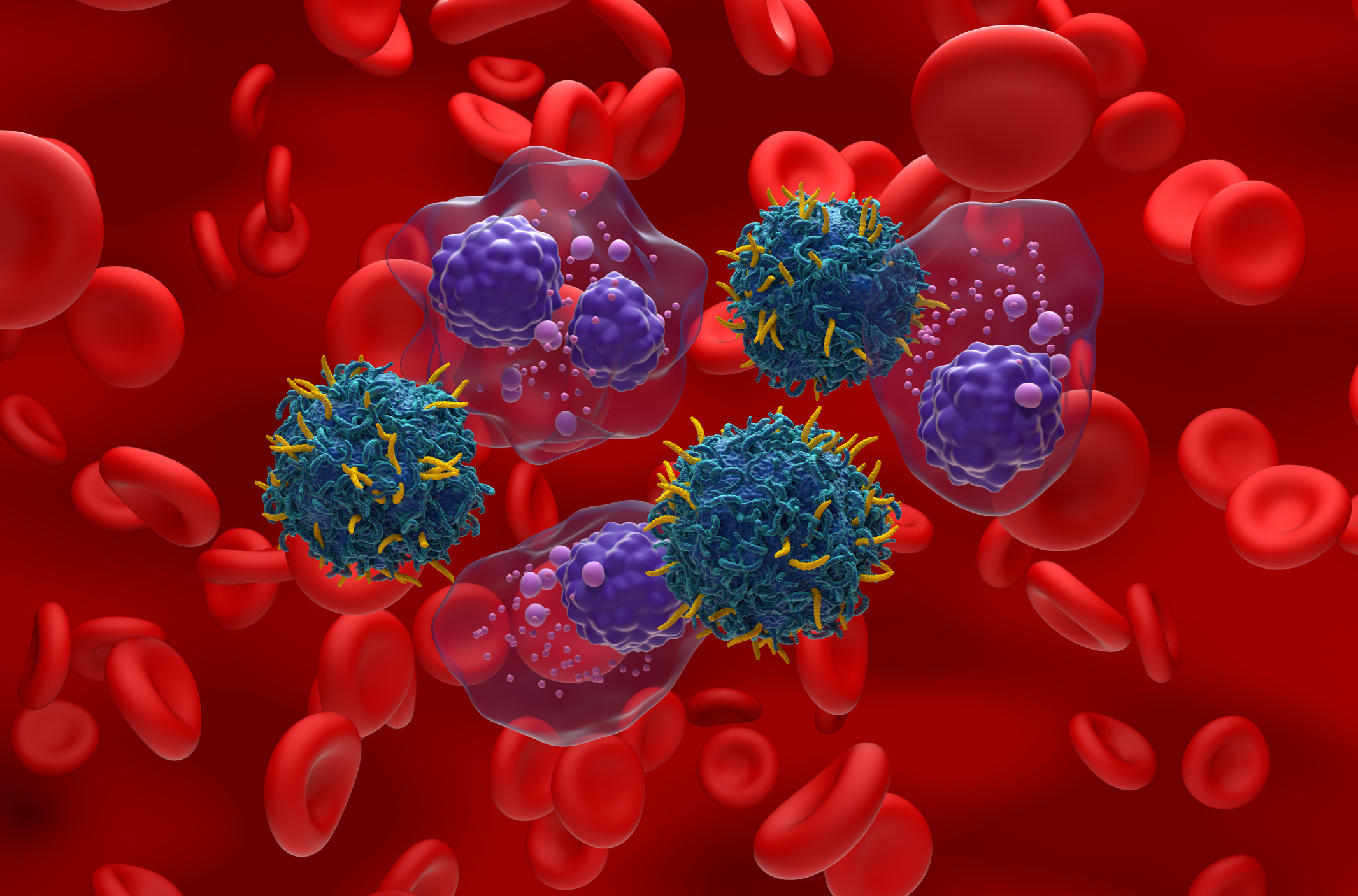

By Cecilia Brown - Last Updated: July 18, 2023HOUSTON — Autologous chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies have shown “unprecedented efficacy” in patients with lymphoma, but new research is addressing remaining challenges and exploring new avenues to improve patient outcomes, said Sattva Neelapu, MD, of the MD Anderson Cancer Center, during a plenary presentation at the 10th Annual Meeting of the Society of Hematologic Oncology.

The United States Food and Drug Administration has approved multiple CD19-directed CAR-T therapies—axicabtagene ciloleucel, tisagenlecleucel, and lisocabtagene maraleucel—for use in patients with relapsed/refractory large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL), follicular lymphoma, and mantle cell lymphoma.

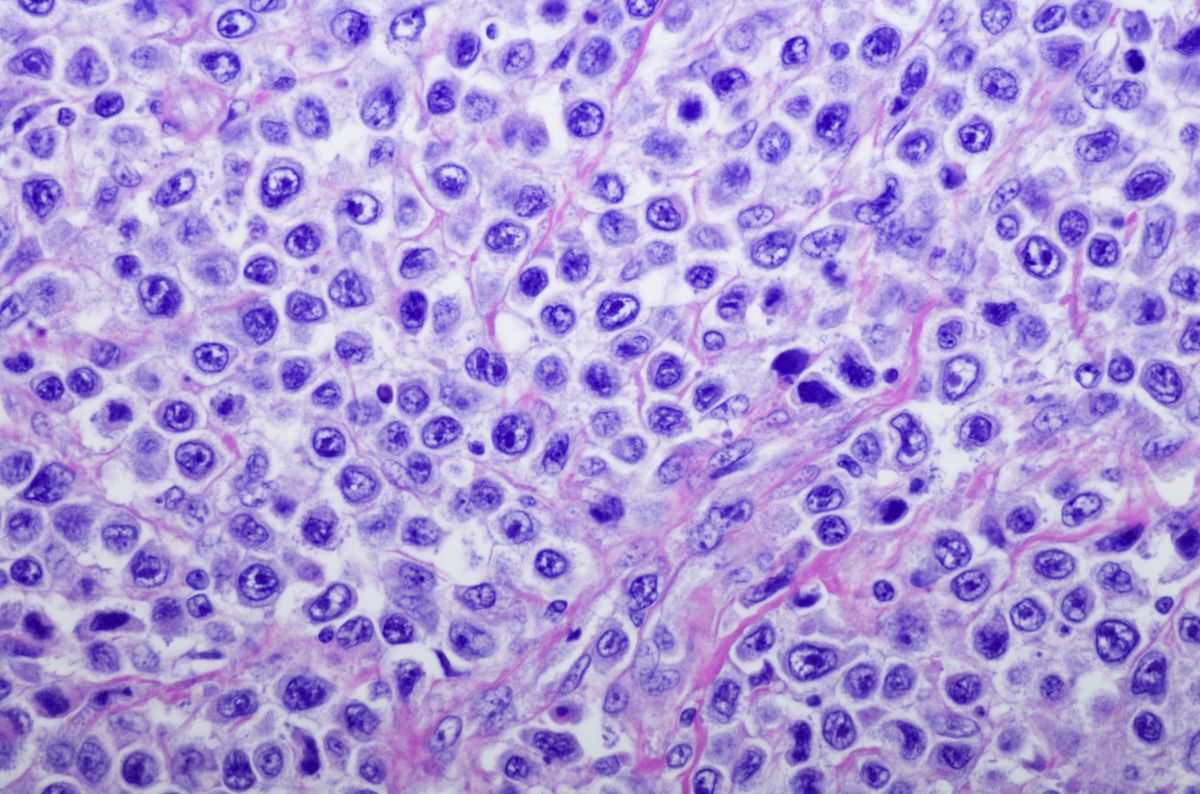

“If you focus on the large B-cell lymphoma trials, you’ll notice that—both in the second line, as well as in the third line—about 40% of patients seem to have long-term durable responses, suggesting that these patients are likely cured,” Dr. Neelapu said. “But the important question going forward is, ‘Why do 60% of these patients relapse?’”

To address this question, it’s key to understand the host-related, tumor-related, and CAR-T-related factors that impact CAR-T efficacy in patients with lymphoma.

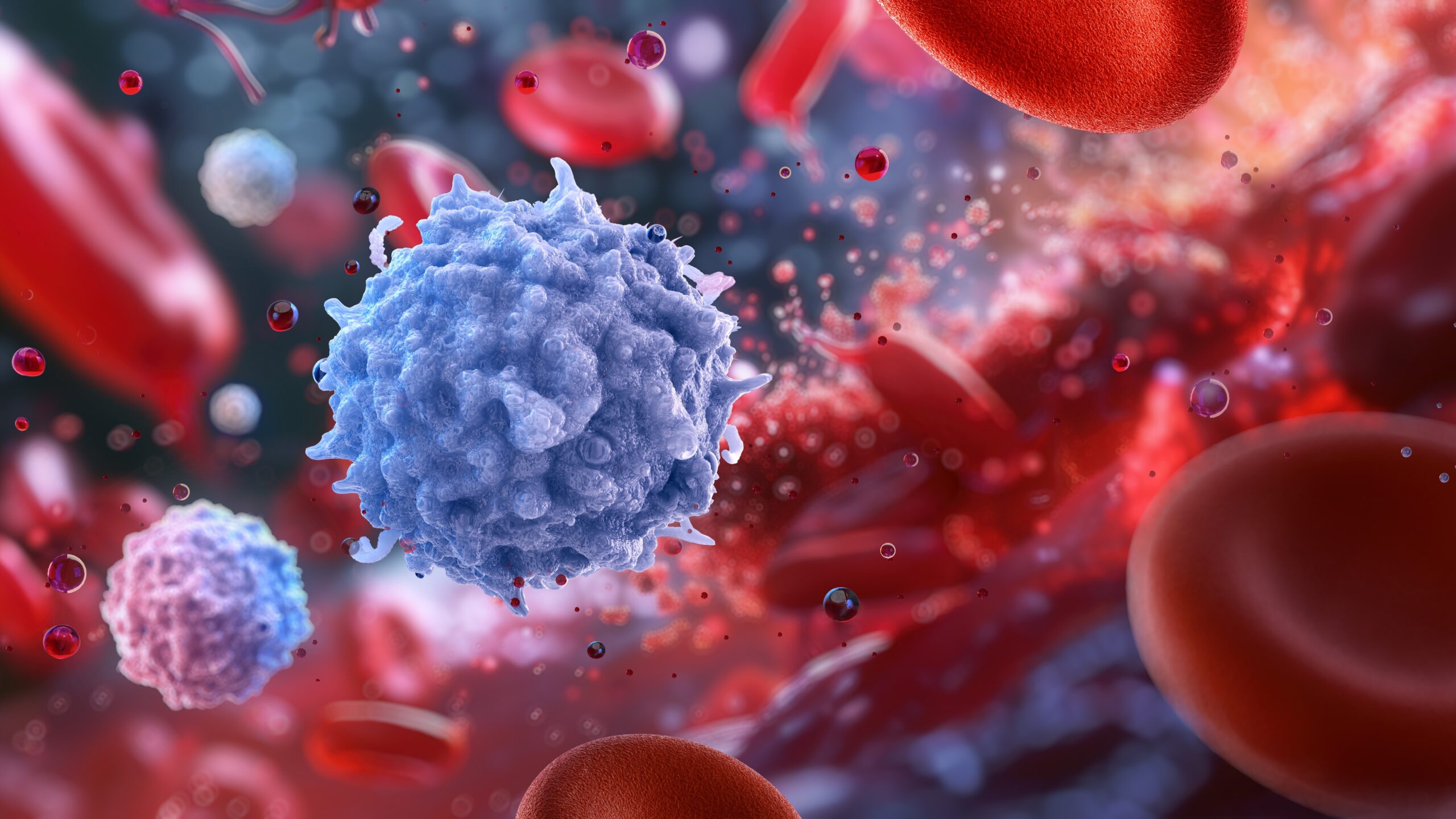

Host-related factors impacting CAR-T efficacy include the patient’s age/performance status, comorbidities, inflammatory state, use of prior therapies, microbiome diversity, and T-cell fitness.

“With respect to T-cell fitness, there are a number of groups that have shown that T-cell fitness in the apheresis product, as well as within the CAR-T product, is important,” Dr. Neelapu said.

Tumor-related factors impacting CAR-T efficacy include the tumor burden, antigen density, antigen loss, and tumor microenvironment. For example, tumor-intrinsic mechanisms associated with CD19 CAR T-cell resistance in patients with LBCL include CD19 loss, CD58 alteration, TP53 genomic alterations, DNA copy number alterations, and complex genomic features.

CAR-T-related factors such as the CAR-T dose, binder, signaling domains, phenotype, polyfunctionality, and composition can also impact patient outcomes.

With the variety of factors that influence CAR-T efficacy, there isn’t a “one-size-fits-all” approach to improving patient outcomes, meaning “there a number of different strategies that we’ll need to explore,” Dr. Neelapu said.

For example, in patients with LBCL who have CD19-negative relapses, targeting multiple antigens with products such as CD22, CD19-CD22, or CD19-CD20 CAR-T could be a potential strategy.

However, CD19-positive relapses are more common, as around two-thirds of patients with LBCL experience that type of relapse, Dr. Neelapu said. In those patients, it’s critical to improve CAR T-cell fitness, he said.

There are a variety of approaches to improving CAR T-cell fitness. At the apheresis level, potential strategies include using specific T-cell subsets or using an allogeneic source of T-cells from a healthy donor.

Early data on allogeneic CAR-T therapies “showed that these products are safe and response rates are comparable to autologous CAR-T products,” Dr. Neelapu said. “However, longer follow-up is needed to assess durability of responses.”

Altering the CAR-T product is another potential strategy, as changing the design of the molecule or the manufacturing technique can address certain challenges. For example, a novel two-day manufacturing process can preserve naïve T-cells, he said.

Adjusting the timing of CAR-T therapy can also impact its effectiveness.

“We know that T-cell fitness could be affected by chemotherapy and probably by the disease as well, so moving CAR T-cell therapy to earlier lines [of therapy] might potentially improve outcomes,” Dr. Neelapu said.

For example, a comparison of patients with LBCL who were treated with axicabtagene ciloleucel as a third-line treatment in ZUMA-1, versus those who received it as a second-line treatment in ZUMA-7, and those who received as first-line treatment in ZUMA-12, showed that complete response and progression-free survival rates improved as the therapy was moved to earlier lines of treatment, he said.

“I just think that moving CAR T-cell therapy to earlier lines may improve outcomes because of improved T-cell fitness,” Dr. Neelapu said. “And consistent with that, when we phenotype the CAR-T products in ZUMA-12 in the first-line setting, we find that these CAR-T products have a higher proportion of naïve-like T-cells, a phenotype that has previously been associated with better clinical efficacy.”

Other potential strategies include using pre-infusion conditioning therapy with fludarabine-based or tyrosine-kinase-inhibitor-based conditioning, and post-infusion conditioning therapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors or immunomodulators.

While challenges and questions remain, novel approaches to improving CAR-T efficacy continue to evolve, with new research addressing relevant host-related factors, tumor-related factors, and CAR-T-related factors that can improve therapeutic outcomes, Dr. Neelapu concluded.

© 2025 Mashup Media, LLC, a Formedics Property. All Rights Reserved.

© 2025 Mashup Media, LLC, a Formedics Property. All Rights Reserved.